You know the pattern.

There's the parent whose needs organize the entire family's schedule. The team lead whose approval everything waits on. The friend whose emotional state determines whether the group can relax. The colleague who somehow holds veto power over decisions they're not officially authorized to make.

When we talk about power imbalance in relationships, we usually frame it as a personality problem. Someone is too controlling. Someone is too passive. Someone needs to set better boundaries. Someone needs to be more assertive.

We send people to therapy to work on their individual patterns. We coach them on communication skills. We tell them to advocate for themselves, to delegate better, to stop people-pleasing.

And sometimes? Nothing changes.

Not because people aren't trying. But because we're trying to fix a structural problem with individual solutions.

The Architecture of Influence

Here's what network science reveals: power doesn't just live in people. It lives in position.

When someone becomes a critical node in a network, the person through whom most information flows, the person most connections depend on, the person whose presence or absence fundamentally changes system behavior, they accumulate influence regardless of intention.

This is centrality. And it creates dynamics that no amount of personal boundary-setting can resolve.

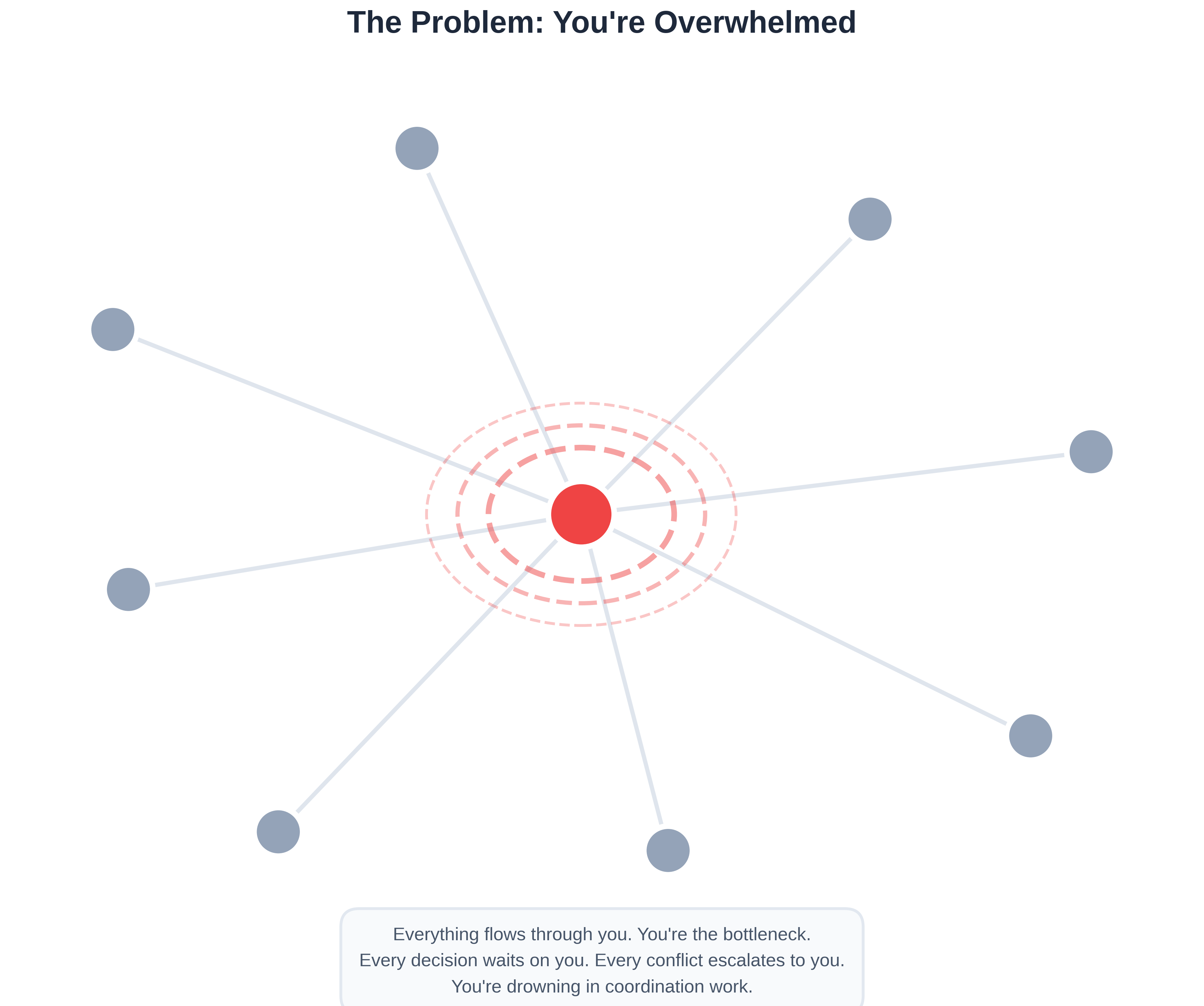

Think about the manager who becomes a bottleneck. Every decision needs their input. Every conflict escalates to them. Every question routes through them. They're not trying to control everything; in fact, they're probably drowning. But the network structure has made them indispensable, and that structural position generates power whether they want it or not.

Or the family member whose emotional volatility everyone learns to manage around. The network reorganizes itself to minimize disruption. People start checking in with each other before raising certain topics. Side channels form. Information flow becomes constrained. The person doesn't need to explicitly demand this arrangement, the network adapts to structural reality.

This is what individual-level psychology misses: the shape of the network itself creates and maintains imbalance.

When "Flat" Structures Hide Hierarchies

Organizations love to announce they're "flat." Families claim everyone's voice matters equally. Friend groups insist there's no leader.

But network analysis tells a different story.

You can map actual communication patterns, for instance who talks to whom, who gets consulted, whose input changes outcomes, and discover invisible hierarchies that have nothing to do with org charts or stated values.

Some patterns you might recognize:

The Star Network: One central node connected to everyone, but people on the periphery barely connected to each other. Officially "collaborative." Actually: complete dependence on the center. When the center is unavailable, the whole system stalls.

The Clustered Network: Tight subgroups with sparse bridges between them. Information pools in silos. The person who bridges clusters accumulates enormous informal power, they control what gets shared across boundaries.

The Chain: Information flows linearly. Break one link, lose whole segments. The person positioned at the junction point between segments can gate-keep, filter, or completely block flow.

None of these require anyone to be trying to dominate. The structure creates the imbalance.

Why Boundaries Don't Solve Structural Problems

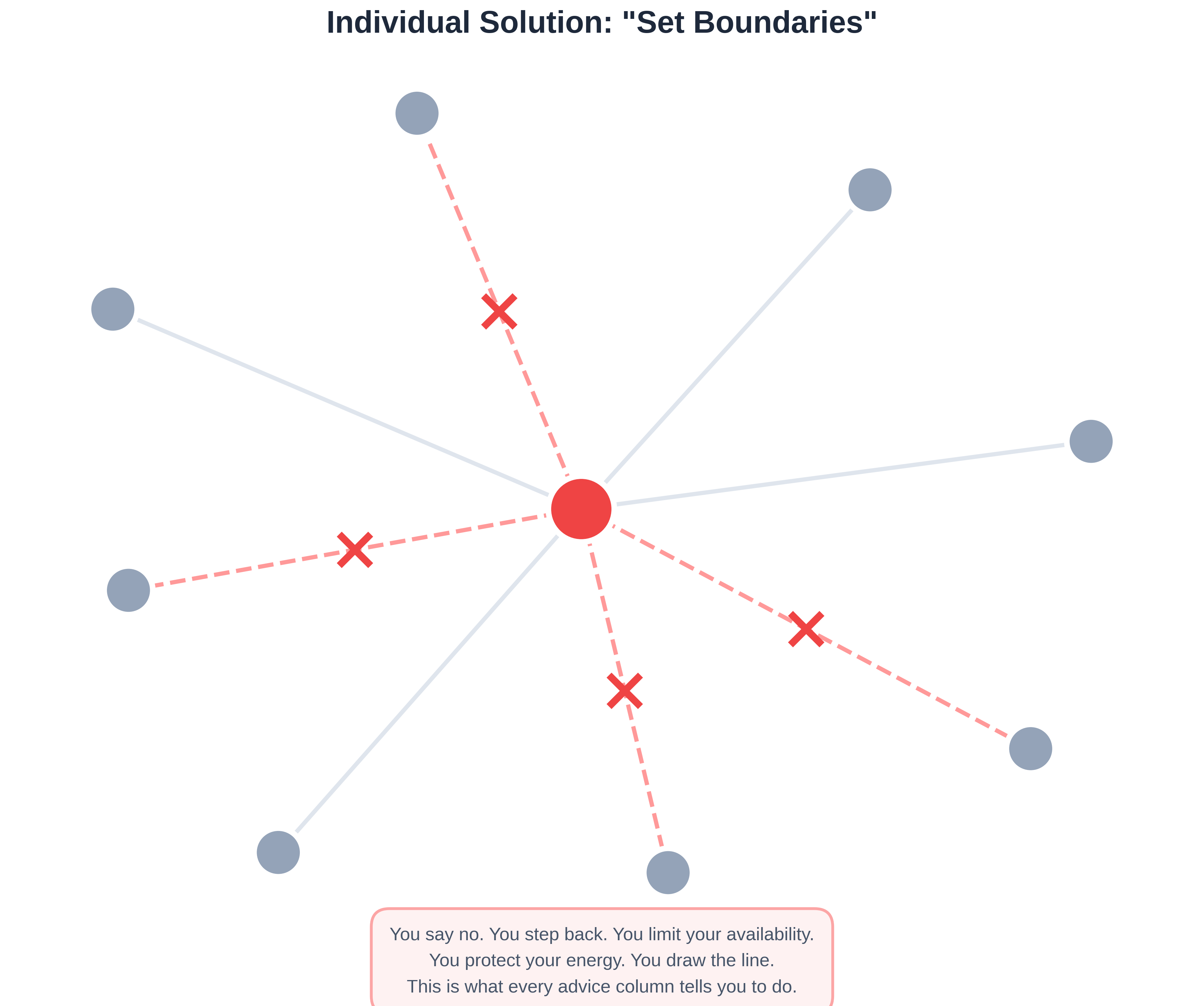

"Just set boundaries" assumes the problem is individual capacity or willingness.

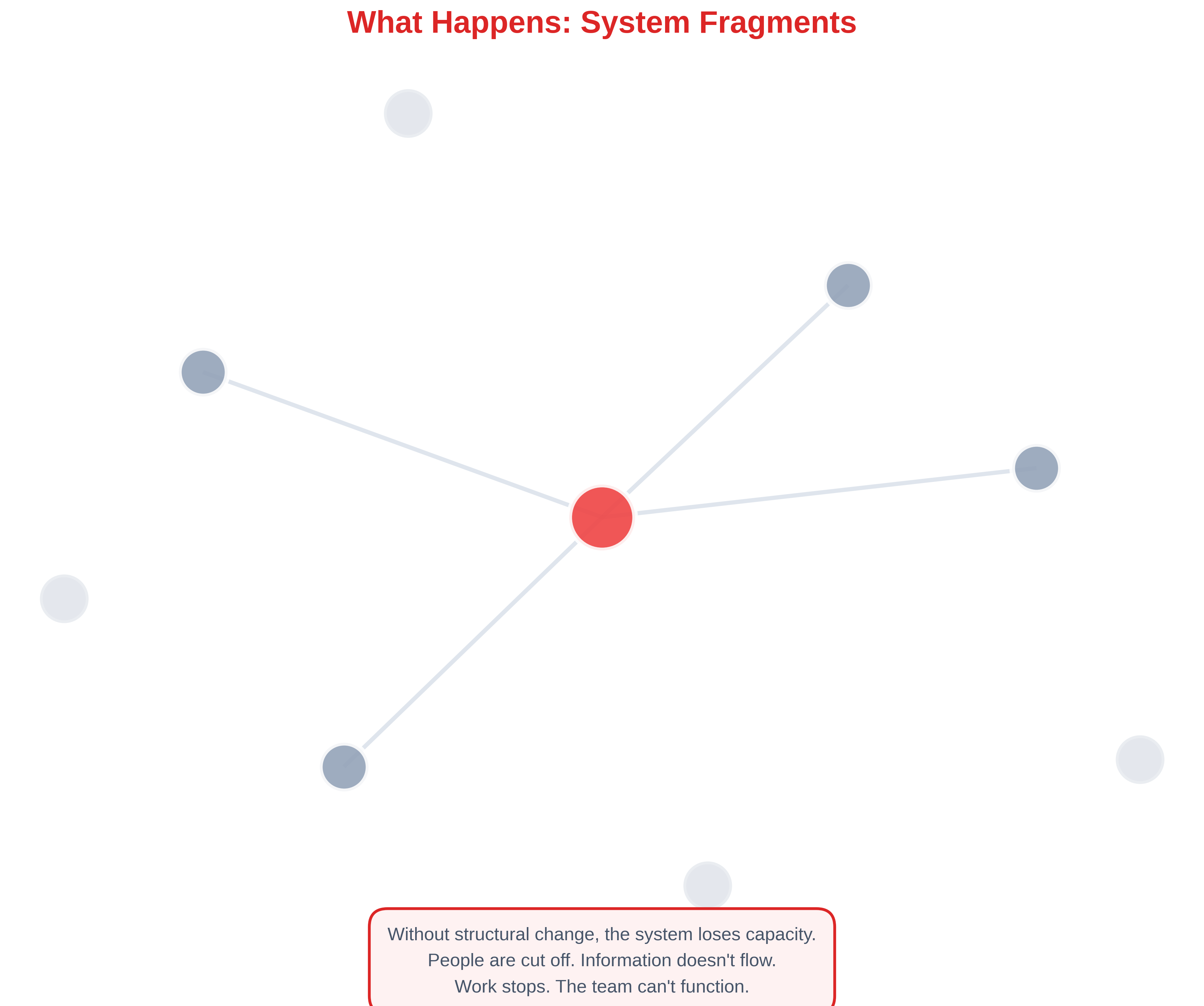

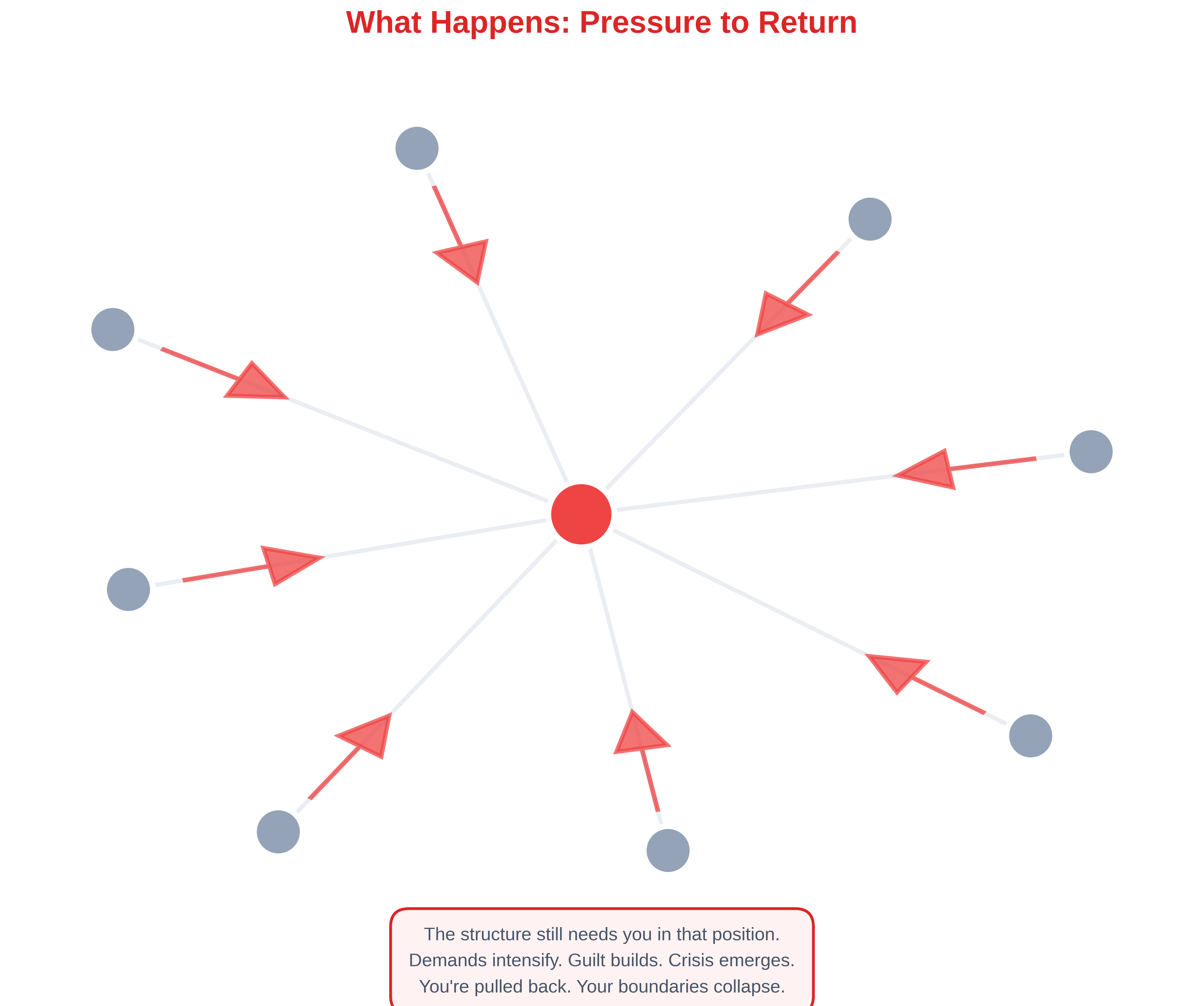

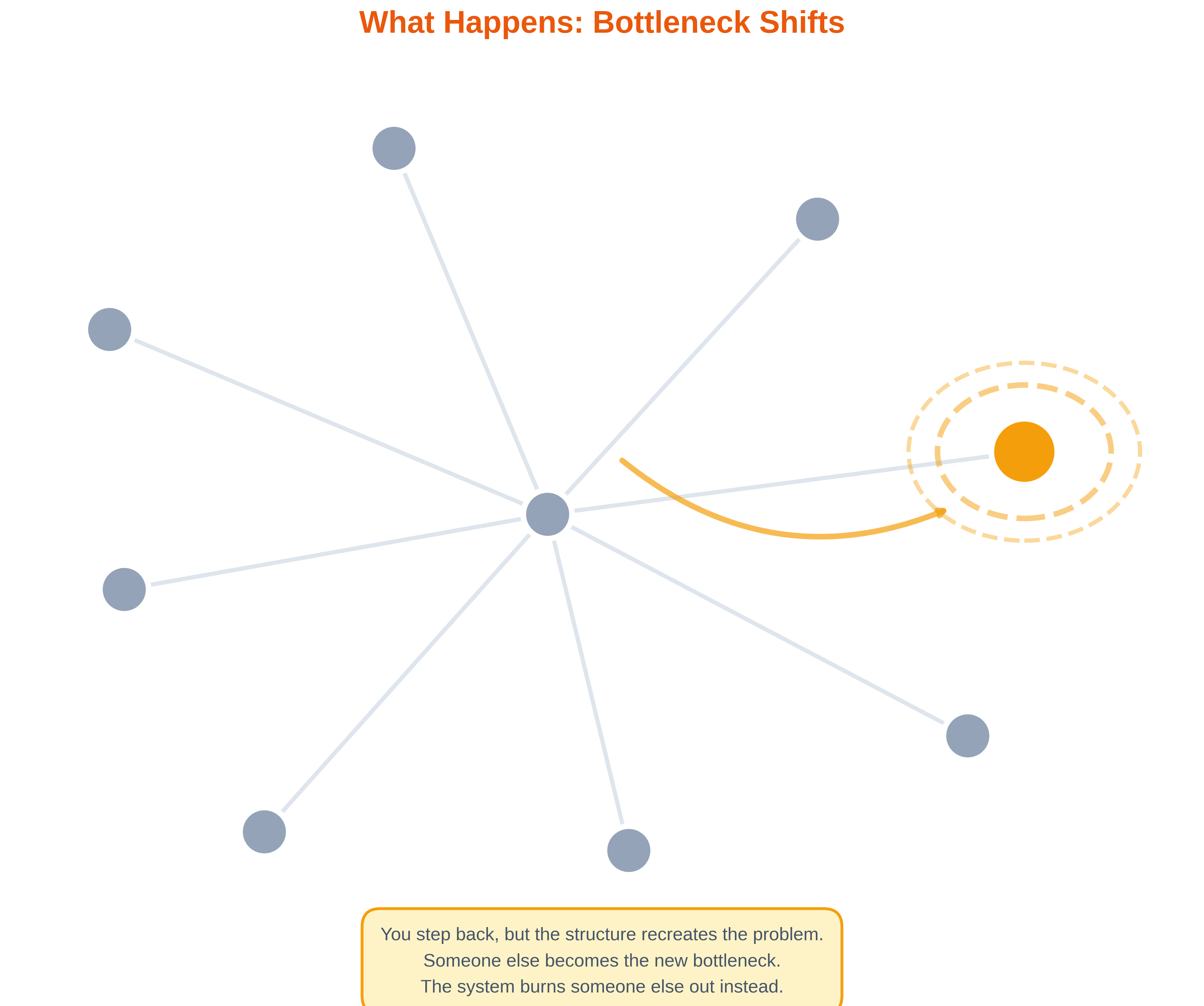

But what happens when you're the only bridge between two parts of a network that need to coordinate? Setting boundaries might protect you temporarily, but it doesn't resolve the structural dependency. The system will either route around you (if possible) or pressure you back into position (if not).

What happens when you're in a family where one person's needs genuinely do require more accommodation, like chronic illness, disability, crisis, but there's no structural support to distribute that load? Telling everyone to "advocate equally for their needs" doesn't create the missing infrastructure.

What happens when a team has a genuine skills imbalance, and one person actually is the only one who can do certain critical things? Individual boundary-setting doesn't build capacity elsewhere. It just exposes the structural vulnerability.

This is why relational work that ignores network structure often fails. You can't redistribute power that lives in architecture by adjusting individual behavior alone.

What Systems Thinking Offers

When you start seeing relationships as networks, different intervention points become visible:

Instead of asking "Why is this person so controlling?" Ask: "What dependencies in this network structure make their position central? What would need to change for influence to distribute differently?"

Instead of asking "Why can't they assert themselves?" Ask: "What would it take for this person's position in the network to carry more structural weight? What connections or capabilities are missing?"

Instead of asking "Why do I keep getting pulled into this role?" Ask: "What pattern in this network keeps recreating this position? What would interrupt that structural tendency?"

You're no longer debugging personalities. You're examining architecture.

And architecture can be redesigned.

The Relational Ecosystem Level

Here's what gets interesting: once you see network structure, you start noticing patterns across domains.

The person who's a bottleneck at work might also be the emotional center of their family and the organizer of their friend group. Not because they have a controlling personality, but because they're skilled at coordination, and networks naturally concentrate coordination functions.

The person who struggles to be heard might be structurally peripheral in multiple contexts, not because they lack worth, but because they haven't developed the connections, the bridging capacity, or the information access that creates structural influence.

These patterns replicate because we don't see them as structural. We think we're dealing with personality traits, when we're actually dealing with network positions we keep recreating.

Relational well-being isn't just about individual relationships. It's about the health of entire ecosystems.

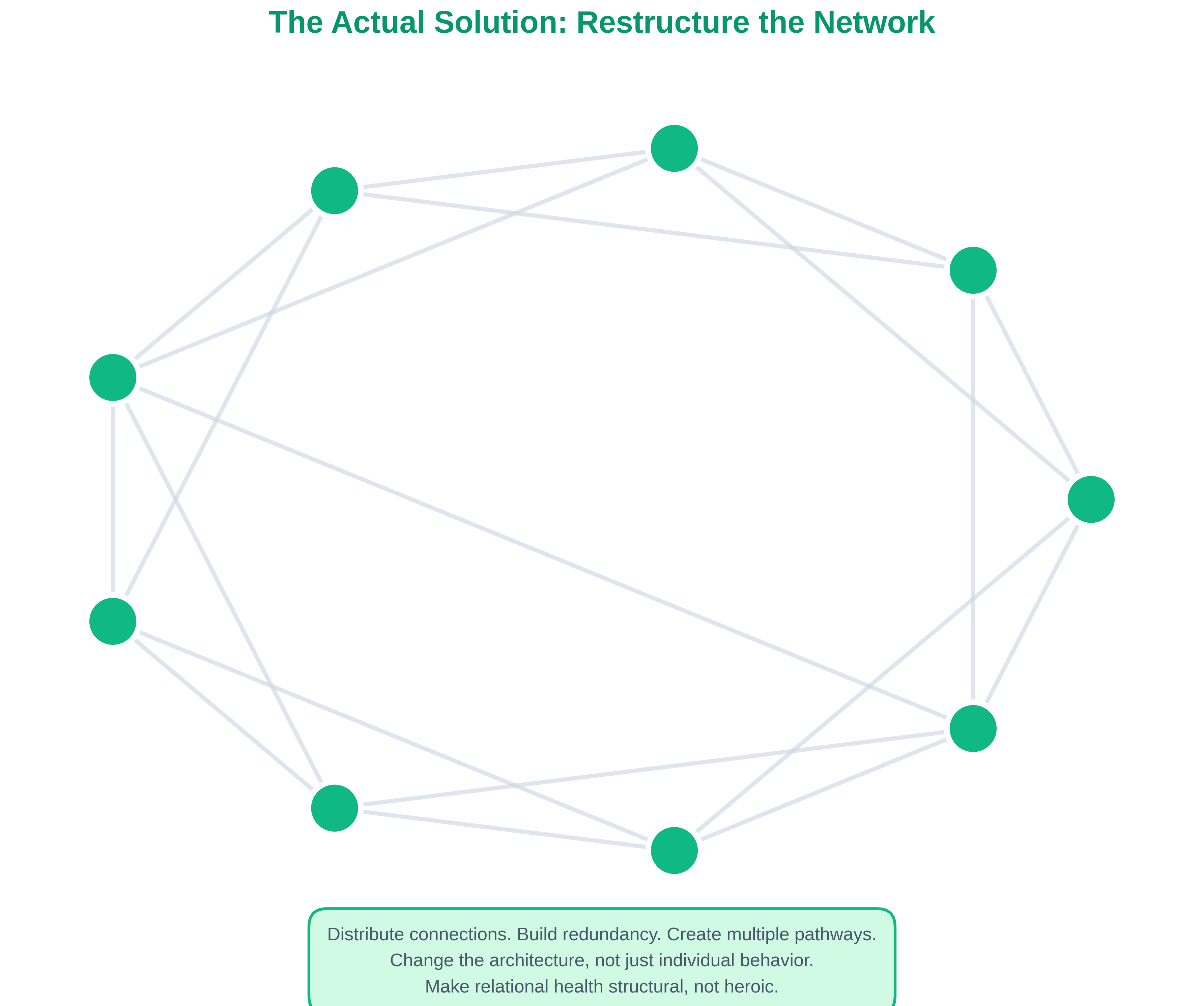

Healthy networks have:

- Distributed centrality (multiple centers, not single points of failure)

- Redundant pathways (information and support can flow through multiple routes)

- Appropriate clustering (local cohesion without isolation)

- Structural balance (stable patterns that don't require constant individual compensation)

When these properties exist, relational health becomes easier to maintain. When they're absent, even highly skilled individuals struggle.

Learning to See the System

Most of us have never been taught to think about relationships this way.

We learn psychology, how individuals work. We learn communication skills and how to interact better. We learn conflict resolution and how to repair ruptures.

We rarely learn systems thinking, which is how to recognize the structural patterns that shape what's even possible in the first place.

But once you learn to see networks, you can't unsee them.

You start noticing when you're being asked to solve a structural problem with individual effort.

You start recognizing bottlenecks before they become crises.

You start asking different questions about why certain dynamics persist despite everyone's best intentions.

You develop a vocabulary for something you've always sensed but couldn't quite name: the architecture of connection itself.

Explore This Further

If you're curious about understanding your relationships through this systems lens, where imbalance lives in structure, not just behavior, I'm offering a Relational Well-Being & Level 1 Seminar on Saturday, April 4th, 1:00-2:30 PM EST.

We'll explore:

- How network structure influences support, belonging, and burnout

- Common relational patterns that create isolation or overload

- Systems-level approaches to healthier relational ecosystems

- Frameworks for seeing structural vulnerabilities and bottlenecks

This isn't therapy or advice. It's a research-informed introduction to thinking about relationships differently, through the lens of networks, systems, and collective dynamics.

All proceeds support independent research at the Hidden Information Labs Institute.

This seminar is educational in nature and does not constitute therapy, counseling, or professional advice. See full disclosures at registration.