Picture the Mediterranean in 600 BCE as a graph, a mathematical structure consisting of nodes (cities) and edges (routes connecting them), with 150+ nodes and thousands of weighted edges. An edge weight represents the "cost" of traversing that connection, measured in time, resources, or difficulty (Diestel, 2017). Nobody planned it this way. No central authority decreed "Miletus shall be a philosophical hub" or "Alexandria will house all human knowledge." Yet the system self-organized with mathematical precision, driven by one brutal constraint: the cost function of moving mass across space.

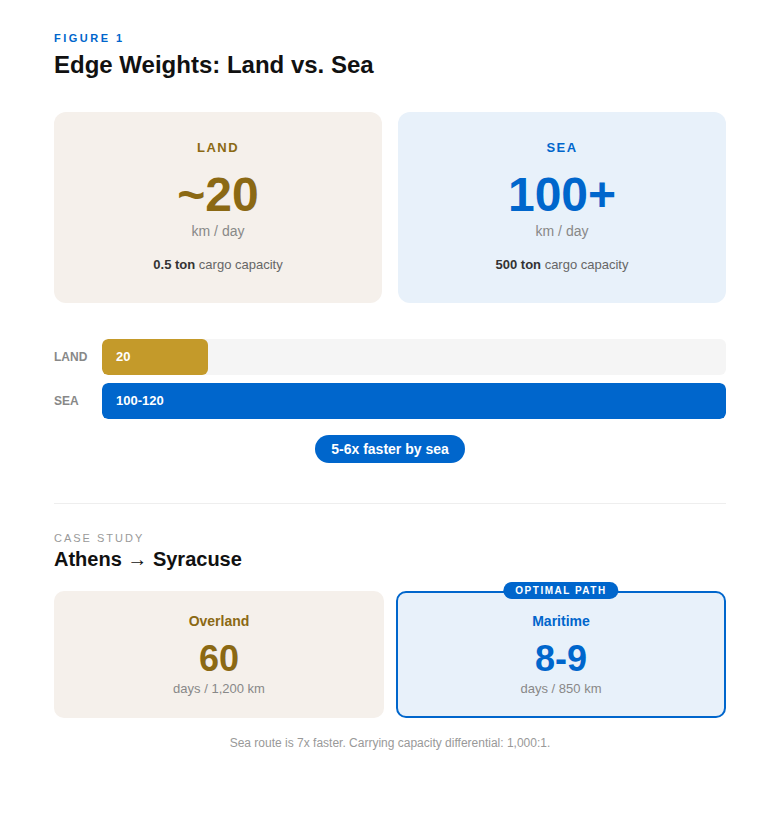

The constraint was geography. Greek mountainous terrain created edge weights of ~20 km/day for overland travel (Casson, 1974). Maritime routes? 100-120 km/day with favorable conditions (Casson, 1951). This 5-6x differential was not marginal; it fundamentally altered network topology, the arrangement and connection pattern of nodes within a network (Newman, 2010). In terms of Dijkstra's algorithm, a method for finding the shortest path between nodes by minimizing cumulative edge weights, the sea provided edges with costs so low that optimal paths between any two points almost always routed through coastal nodes, even when the geometric distance was greater (Cormen et al., 2009).

Concrete example: Athens to Syracuse. Overland through the Peloponnese, across to Corcyra, down the Adriatic coast: perhaps 1,200 km at 20 km/day = 60 days minimum, assuming perfect conditions and no obstacles. By sea: 850 km at 100 km/day = 8-9 days of actual sailing. The sea route was 7x faster despite careful coastal navigation (see Figure 1).

It was not so much that the Greeks weren't good sailors (though they were), but about the sheer physics that made these feats possible. For instance, from a physics standpoint, water friction is negligible compared to rolling a wagon over rocky terrain. A merchant ship could carry 500 tons (Casson, 1995), while an ox-cart may carry half a ton in weight. The carrying capacity differential was 1000:1. Think about it…

Preferential Attachment and the Emergence of Hubs

Network science tells us that in systems where new connections preferentially attach to well-connected nodes, a phenomenon where popular nodes gain new connections at higher rates than less-connected nodes (Barabási & Albert, 1999), you get power-law distributions: a few superhubs, many minor nodes. The Greek maritime network evolved exactly this pattern.

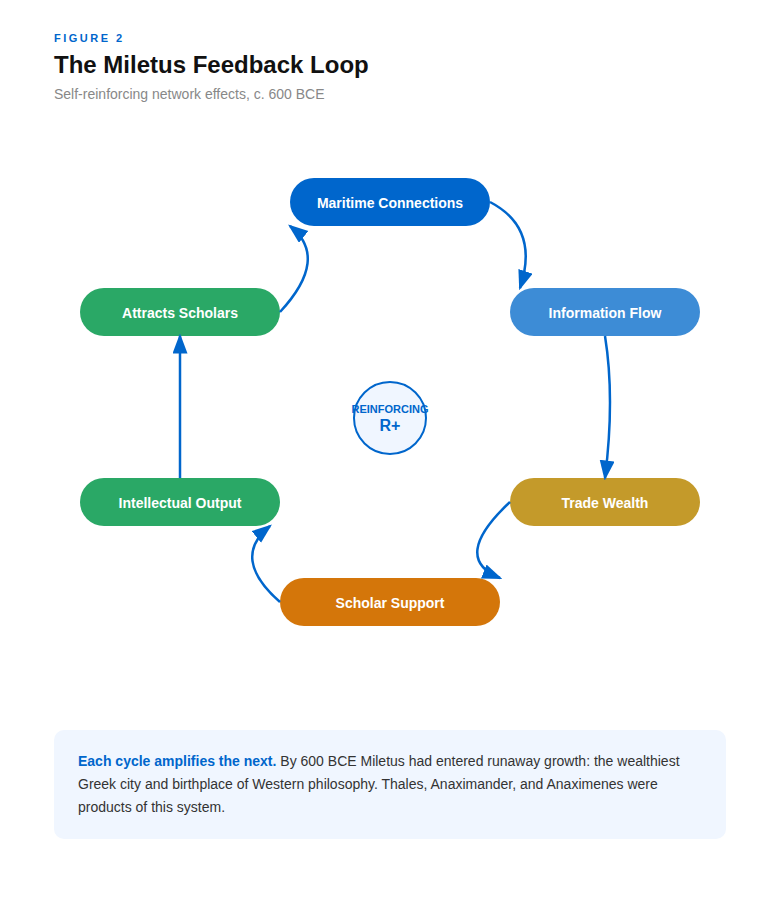

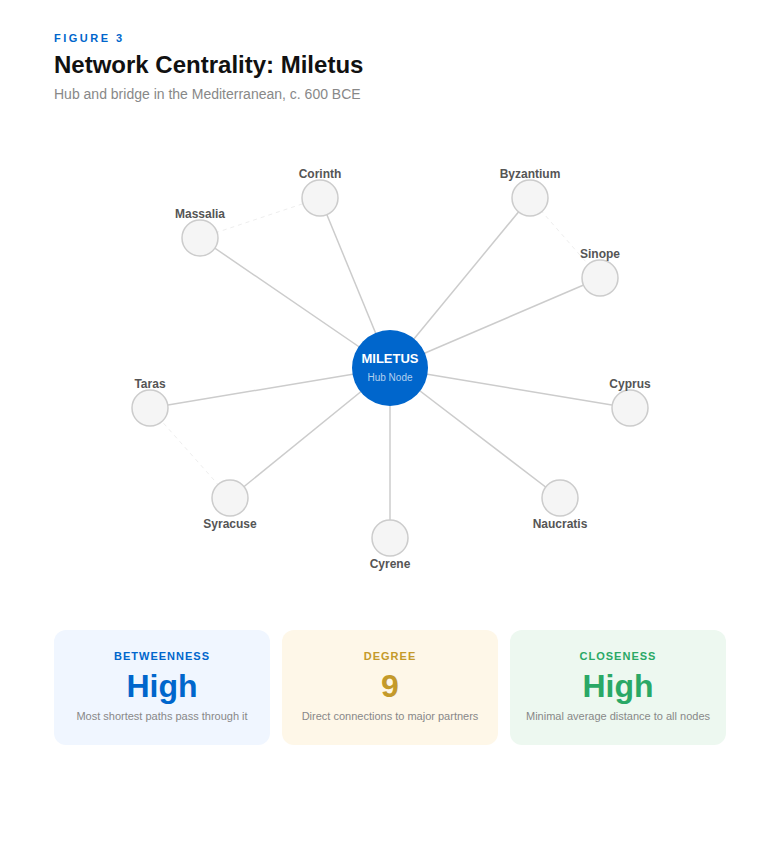

Miletus (c. 600 BCE) became the first philosophical hub through pure network mechanics. Located at the mouth of the Maeander River on the Ionian coast, it had edges to Egypt, Phoenicia, the Black Sea colonies, and western Greece (Greaves, 2002). By 600 BCE, it founded 90+ colonies itself (Boardman, 1999), each creating new trading edges back to the mother city.

Here's the systems dynamic, a feedback loop where outputs feed back as inputs, creating self-reinforcing cycles (Meadows, 2008): Thales (c. 624-546 BCE) was not brilliant in a vacuum.

He operated in a city where ships from Naucratis (Egypt) docked next to vessels from Olbia (Black Sea) and Massalia (France). Egyptian geometry, Babylonian astronomy, Persian cosmology: all flowing through the same port (Netz & Noel, 2007). When Thales claimed water was the fundamental substance, he had studied with Egyptian priests who understood Nile flood mechanics (Couprie, 2011). When Anaximander posited the apeiron (the boundless), he was synthesizing concepts from multiple traditions impossible to access in landlocked Thebes.

Network centrality measures: Centrality quantifies how important a node is within a network structure (Borgatti & Everett, 2006). Miletus had high betweenness centrality, a measure of how many shortest paths between other nodes pass through it, and high degree centrality, the number of direct connections to other nodes. In network terms, it was both a hub and a bridge.

Information Cascades: How Ideas Propagated

Let's trace a specific knowledge cascade, a phenomenon where information spreads through a network in sequential steps, each node influencing connected nodes (Easley & Kleinberg, 2010). Pythagoras (c. 570-495 BCE) was born on Samos, an island 60 km from Miletus. Maritime distance meant frequent interaction. He studied in Egypt for ~20 years, learning mathematical traditions (Kahn, 2001). He then traveled to Babylon, accessing different astronomical methods. Finally, he founded his school in Croton, southern Italy, another maritime colony.

The route tells the story: Samos → Egypt → Babylon → Croton. Each leg maritime except Babylon (and even that involved sailing to Phoenician ports, then a shorter overland segment). Pythagoras was not exceptional in traveling; he was typical of how the network operated. Ideas were not spreading through linear diffusion; they were cascading through network pathways with predictable velocity based on edge weights.

Concrete propagation speed: News of Emperor Galba's death traveled from Rome to Alexandria in 27 days, roughly 100 km/day (Hunt & Edgar, 1934). That's information traveling at the network's maximum throughput. Complex ideas moved slower (required unpacking, translation, debate) but followed the same pathways.

The Alexandrian Singularity: When Network Effects Compound

Alexandria (founded 331 BCE) represents what happens when you deliberately optimize network positioning. Alexander chose the location with precision: on the Mediterranean coast, between Lake Mareotis and the sea, connected to the Nile via canal (Fraser, 1972). This gave Alexandria edges to:

- Mediterranean trade routes (east-west)

- Red Sea trade routes via Nile connection (to India, East Africa)

- Nile valley (to Upper Egypt, Nubia)

- Overland routes to Syria and the Levant

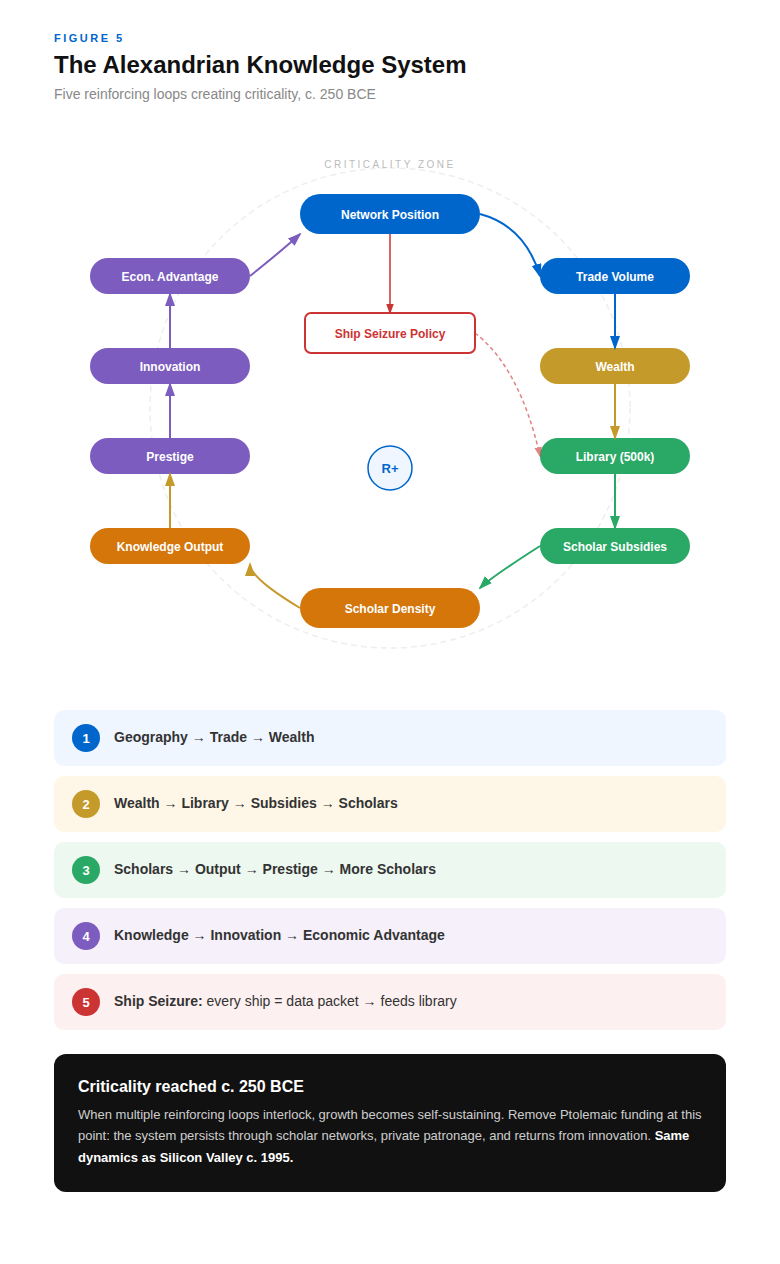

The Ptolemies weaponized network effects. Ptolemy II's ship-seizure decree (Canfora, 1990) was algorithmic: every vessel entering Alexandria's harbor = potential information packet. Books seized, copied by professional scribes, originals kept. This was not cultural imperialism, but systematic network data harvesting.

The numbers reveal the system: By the 3rd century BCE, the library held ~500,000 scrolls (El-Abbadi, 1990). At an average of 20,000 characters per scroll, that's 10 billion characters of data, the ancient world's largest database, concentrated in one hub.

But the real network effect was human capital aggregation, the clustering of skilled individuals in a single location, creating density effects where proximity increases productivity (Florida, 2002). The Mouseion offered salaries, free housing, tax exemption (MacLeod, 2000). If you're Eratosthenes and you can work anywhere, you choose the node with the highest information density. Once Eratosthenes is there, that attracts Archimedes. Once both are there, that attracts Apollonius of Perga. Positive feedback accelerates. Now you've created an attractor that is very difficult to resist.

Systems dynamic: A set of interconnected elements whose interactions produce emergent system-level behaviors that cannot be predicted from individual components alone (Sterman, 2000):

- Geographic network position → trade wealth

- Trade wealth → resource surplus

- Resource surplus → subsidized scholars

- Concentrated scholars → knowledge production

- Knowledge production → greater prestige

- Greater prestige → attracts more scholars → back to step 4

By 250 BCE, Alexandria had achieved criticality, a phase transition where a system shifts from one stable state to another qualitatively different state (Scheffer et al., 2009), in this case, a self-sustaining knowledge reactor.

Redundancy, Failure Modes, and Network Resilience

Here's where network thinking gets interesting. The Greek maritime system had high redundancy, multiple alternative paths between nodes that maintain connectivity when individual routes fail (Albert et al., 2000). If pirates blockaded one route, alternative paths existed. Syracuse to Athens could route through Corinth, or around the Peloponnese, or via Crete. This redundancy made the network resilient to local failures but vulnerable to systemic shocks.

Case study: The Ionian Revolt (499-493 BCE). When Persia crushed Miletus in 494 BCE, literally destroying the city, the philosophical hub shifted to Athens and Abdera (Murray, 1988). The network topology changed, but knowledge flow continued. Anaxagoras fled from Clazomenae to Athens; Democritus operated from Abdera. The information survived node destruction because it had replicated across edges before the failure.

But notice the path dependency, the principle that current outcomes depend heavily on the sequence of past events and decisions (Arthur, 1994): Athens became the next major hub partly because it had strong existing edges to Ionian cities, partly because its naval victory at Salamis (480 BCE) established maritime dominance. Network position shaped which nodes could absorb displaced scholars.

Modern parallel: When university departments face funding cuts, researchers migrate to institutions with resources. The knowledge persists but concentrates differently. Same network dynamics, different substrate.

Practical Network Mechanics: How Information Actually Moved

Abstract network theory is useless without transmission mechanics. Let's get specific.

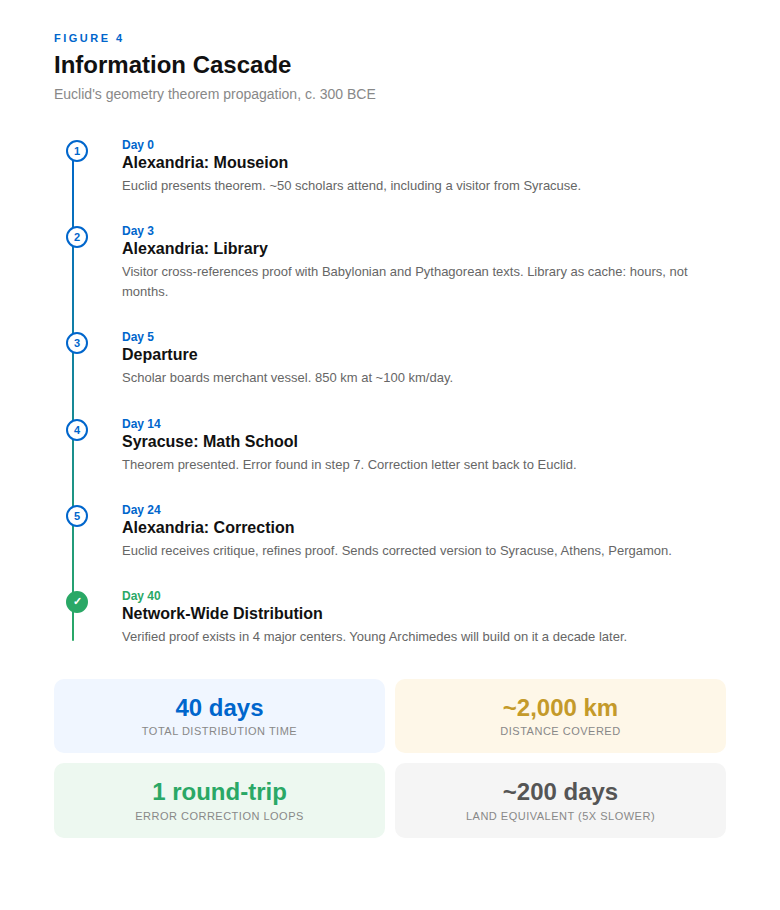

Scenario 1: Mathematical proof propagation Euclid proves a geometry theorem in Alexandria (~300 BCE). How does it reach Syracuse?

- Euclid presents at the Mouseion; maybe 50 scholars present

- Visiting scholar from Syracuse (there on 6-month study) attends lecture

- Scholar returns to Syracuse with notes: 8 days sailing

- Presents findings to local mathematicians

- One student disagrees with a step; sends letter back to Alexandria with ship captain (common practice)

- Euclid's response returns 16 days later

- Refined proof now exists in two nodes; begins spreading to their respective network neighborhoods

Total time: ~2 months for sophisticated mathematical ideas to traverse 850 km and replicate with error-checking. That's bandwidth, the rate of information transfer through a channel, measured in bits per unit time (Shannon, 1948).

Scenario 2: Astronomical observations Hipparchus in Rhodes (c. 150 BCE) observes stellar positions. These observations need Egyptian data for comparison.

- Rhodes to Alexandria: 4-5 days sailing (Casson, 1951)

- Alexandria library has Babylonian astronomical tables (acquired via Ptolemy's ship seizures)

- Hipparchus sends request via commercial ship captain

- Librarian copies relevant sections: 2 days

- Return voyage: 5 days

- Total: ~12 days to access data that would take months to regenerate through observation

The library functioned as a centralized cache, a local data store that reduces retrieval costs by keeping frequently accessed information nearby (Hennessy & Patterson, 2011), reducing redundant computation across the network.

The Second-Order Effects: What Network Structure Enabled

When you drop information transmission costs by 5-6x and concentrate scholars in high-density nodes, you don't just get faster communication; you get qualitatively different knowledge production. This is emergence, when system-level properties arise that individual components don't possess (Holland, 1998).

Eratosthenes' measurement of Earth's circumference (c. 240 BCE) required:

- Observation in Alexandria: sun angle at summer solstice

- Observation in Syene (800 km south): sun directly overhead at same time

- Communication between sites

- Geometric calculation using the distance and angle difference

Result: 252,000 stadia (~39,375 km) versus actual ~40,075 km, a 2% error (Rawlins, 1982).

This was not brilliant individuals working in isolation. It was a distributed measurement system enabled by:

- Geographic network (Alexandria-Syene Nile connection)

- Institutional network (Mouseion funding)

- Communication network (messengers, documented observations)

- Intellectual network (geometric methods from Euclid, astronomical data from Babylonians)

Remove any component, the measurement fails. This demonstrates system dependency, the concept that complex outcomes require multiple interdependent elements functioning simultaneously (Perrow, 1999).

Archimedes in Syracuse (287-212 BCE) could access Euclid's Elements from Alexandria, apply them to mechanical problems, then send his Method back to Alexandria for preservation (Netz et al., 2011). He operated as a distributed node in a collaborative network, not an isolated genius.

Network Topology and the Geography of Ideas

Certain ideas could only emerge in high-centrality nodes. Stoicism developed in Athens, not Sparta. Why? Athens had edges to Phoenicia (Zeno was from Citium in Cyprus), to Egypt, to Ionia (Long, 1986). Zeno could synthesize Cynic philosophy (Greek) with elements of Phoenician cosmology. Sparta, landlocked and isolationist, had low degree centrality: few edges, low information diversity.

Heraclitus of Ephesus (c. 535-475 BCE): "You cannot step into the same river twice" (fragment DK22B12). This was not random insight; Ephesus was a major port where he observed constant flux: ships arriving, departing, goods flowing through, merchants from dozens of cultures (Graham, 2019). The environment shaped the philosophy. His fundamental insight about change mirrored the system he inhabited.

Contrast with Parmenides of Elea (southern Italy), who argued nothing changes, all is one unchanging Being (Palmer, 2020). Elea was more isolated, smaller node, less traffic. The network position correlates with philosophical content.

This is not determinism; individual genius mattered. But network position constrained the possibility space of ideas, the range of concepts accessible given available information inputs (Kauffman, 1993).

The Failure Mode: What Happened When the Network Broke

The Library of Alexandria burned multiple times: partially under Caesar (48 BCE), progressively degraded, largely destroyed by 3rd century CE (El-Abbadi, 1990). But the deeper failure was network collapse, the breakdown of interconnections that sustained information flow.

As Rome centralized power, the distributed Greek network model weakened. Knowledge concentrated in Rome, but Rome was not positioned as optimally as Alexandria; it was a political hub forced to function as intellectual center. The maritime network persisted, but the feedback loops that concentrated scholars in high-density nodes deteriorated.

Hypatia's murder (415 CE) in Alexandria symbolizes the transition (Dzielska, 1995). When religious authorities killed her, they were not just killing a mathematician; they were severing network connections. Her students dispersed; the collaborative environment collapsed. The node's centrality decreased, information flow reduced, the self-reinforcing cycle reversed.

By 642 CE when Arabs conquered Alexandria, the network was already fragmented. The city remained a trade hub, but the knowledge-production system had dissipated. The infrastructure (harbor, location) persisted; the network effects had collapsed.

Modern Parallels: Network Principles Are Substrate-Independent

Academic citation networks follow power-law distributions: a few papers get massive citations, most get few (Price, 1976). The "Matthew effect," where initial advantages compound over time (Merton, 1968), is pure preferential attachment. Papers with citations attract more citations, not because they're proportionally better, but because they're more visible in the network.

The internet itself: Before fiber-optic cables, information transmission was expensive (edge weight high). Email reduced transmission costs by ~1000x. This did not just make communication faster; it enabled Wikipedia (distributed knowledge aggregation), GitHub (collaborative code development), arXiv (preprint sharing). The cost reduction changed what kinds of knowledge systems could exist, a phase transition identical to what maritime routes enabled for ancient Greeks.

Dijkstra's Algorithm as Historical Metaphor

If we look at Dijkstra's algorithm, a graph search method that finds the shortest path between nodes by iteratively selecting the path with the minimum cumulative weight (Dijkstra, 1959), we can make an interesting connection. The ancient Greeks were solving a shortest-path problem: How do I get knowledge from Egypt to Athens? How do I get grain from the Black Sea to Corinth? How do I get philosophical training if I'm born in Sicily?

The algorithm:

- Assign weights to edges (travel time, cost, risk)

- Find paths minimizing total weight

- Optimize iteratively

But they did not just use the algorithm; they were the algorithm. The network self-organized around the cost function. High-cost edges (mountain passes) were avoided; low-cost edges (sea lanes) saw heavy traffic. Nodes on optimal paths (Miletus, Athens, Alexandria) became hubs automatically through preferential attachment.

The insight: Network topology is not separate from content. The structure of information flow shapes what information flows. The Greeks became "disseminators of knowledge" not because they were inherently superior, but because they happened to optimize a network where maritime routes reduced transmission costs enough that knowledge concentration became possible.

Take Thales, born in exactly the right place (Miletus) at exactly the right time (600 BCE when trade networks matured). Move him to landlocked Arcadia, and he's a shepherd. The network position enabled the genius, not vice versa.

Systems Thinking: Emergence and Phase Transitions

Here's the conceptual leap: we don't need to posit Greek exceptionalism, but we do need to recognize that when information transmission costs drop below a threshold, knowledge systems undergo phase transitions, discontinuous changes in system state when a control parameter crosses a critical value (Strogatz, 2018).

Pre-600 BCE: High transmission costs → knowledge local → limited synthesis → slow advancement

600-300 BCE: Lower transmission costs → knowledge mobile → cross-pollination → accelerating returns

300 BCE-200 CE: Concentrated nodes + institutional support → knowledge production becomes self-sustaining → explosive growth

This is emergence. No individual Greek said "Let's create Western philosophy." They responded to local incentives within a network structure, and the aggregate behavior produced something none of them planned. This is identical to how market economies emerge from individual self-interested trades, or how termite colonies build sophisticated structures through local rules (Johnson, 2001).

The modern lesson: We're experiencing another phase transition now. Pre-internet transmission costs = libraries, journals, conferences. Post-internet transmission costs ≈ zero. We're watching real-time emergence of new knowledge structures (Wikipedia, open-source software, preprint servers) that nobody designed centrally but that emerge from individuals responding to changed cost functions.

The Greeks navigated their network on wooden ships. We navigate ours on fiber-optic cables. The substrate changed; the mathematics didn't. AI tools are just the next reduction in the cost of moving information. To be continued…