Picture a patient with multiple chronic conditions discharged from the hospital. She carries a stack of papers, a new medication list, and appointments with several specialists. Her primary care physician receives a truncated summary weeks later; her community nurse never sees the cardiologist's report. Each clinician is dedicated, yet no single person holds the complete narrative.

This is the reality of fragmented healthcare. And through the lens of network theory, it appears precisely as it is: a system suffering from a failure of connectivity.

Defining the Problem: What Do We Mean by Care Fragmentation?

In health services research, care fragmentation is formally defined as care that is distributed across a large number of clinicians and facilities, with no single provider accountable for a substantial portion of the patient's care or information [1].

The consequences are measurable and sobering:

An analysis of U.S. readmissions from 2018 to 2020 found that 24 to 31 percent of patients were readmitted to a different hospital. These "fragmented readmissions" were associated with an 18 to 20 percent higher odds of in-hospital mortality and nearly one extra day in the hospital, even after adjusting for patient and hospital factors [2].

For patients recovering from major surgery or trauma, being readmitted to a non-index hospital is consistently linked to higher rates of mortality and major complications [3].

Among patients with chronic illnesses, higher outpatient care fragmentation scores correlate with an increased risk of hospital readmission and greater use of acute care services [4].

Conversely, systematic reviews affirm that continuity of care, which involves having a consistent therapeutic relationship and coordinated care, is associated with superior outcomes, reduced hospitalizations, and higher patient satisfaction [5].

In essence, when care devolves into a series of disconnected episodes, patients bear the clinical risk.

A Primer in Network Theory: A New Way to See the System

Network theory provides a powerful framework for understanding complex systems by mapping them as collections of nodes (the actors) and edges (the relationships between them).

Nodes in healthcare can include physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers, clinics, hospitals, home-care agencies, IT systems, and the patients and their families themselves.

Edges represent the flows of information, referrals, shared care plans, and communications. This includes formal EMR messages, referrals, and informal conversations.

A few key concepts help illuminate the structure of these networks:

Degree: The number of connections a node possesses. A primary care physician coordinating multiple specialists typically has a high degree.

Density: The proportion of possible connections that actually exist. A dense, integrated team communicates richly, while a sparse network is characterized by isolated pairs.

Centrality: A measure of a node's importance in the network's flow of information. A ward clerk or care coordinator, for instance, may have high betweenness centrality, acting as a crucial bridge between different professional groups.

Clusters or Communities: Tightly-knit subgroups within the larger network, such as an oncology unit that has limited interaction with primary care or mental health services.

Structural Holes: Gaps or disconnections between clusters where information fails to flow.

The application of social network analysis (SNA) in healthcare settings has, for over a decade, helped visualize these patterns. It reveals hidden communication channels, critical bottlenecks, and isolated parts of the system [6].

From this vantage point, fragmented care is not merely a problem of having "too many providers." It is, fundamentally, a pathology of the network. It is a failure of connectivity, unreliable information pathways, and missing structural bridges.

As the number of care transitions increases, clinical information degrades, elevating the risk of severe errors.

The Anatomy of Fragmentation: Network Patterns in Healthcare

Consider three common, problematic network archetypes:

1. The Siloed Specialties

Distinct, dense clusters form around specialties like cardiology, endocrinology, and psychiatry.

Communication flows freely within each cluster but is sparse and unreliable between them, particularly across organizational boundaries.

Result: A cardiologist optimizes heart failure medications without the context of a psychiatrist's note on cognitive barriers to adherence or a social worker's assessment of food insecurity. Each cluster functions well in isolation, but the patient exists in the gaps between them.

2. The Overloaded Hub

A single node, often the primary care physician or a hospitalist, is positioned as the central coordinator for all care.

Specialists, home care, and community providers connect almost exclusively through this hub, forming a star-like network.

Result: While seemingly efficient, this structure is inherently fragile. If the hub is overburdened, on leave, or hampered by siloed IT systems, communication across the entire network grinds to a halt.

3. The Multi-Agency Mosaic

Health, mental health, social care, and community organizations operate as separate, insular clusters.

Policy rhetoric assumes "collaboration," but few formal edges exist. There may be no shared electronic records, infrequent case conferences, and no designated coordinator.

Result: This system is riddled with structural holes. The gaps between these well-intentioned clusters are where patient needs go unmet and critical information is lost.

Contemporary research applying network theory explicitly frames poor care integration as a direct consequence of these suboptimal structures, which are often shaped by policy and financing decisions [7].

From Broken Networks to Patient Harm: The Causal Pathways

How, precisely, do these network failures translate into worse health outcomes and prognoses?

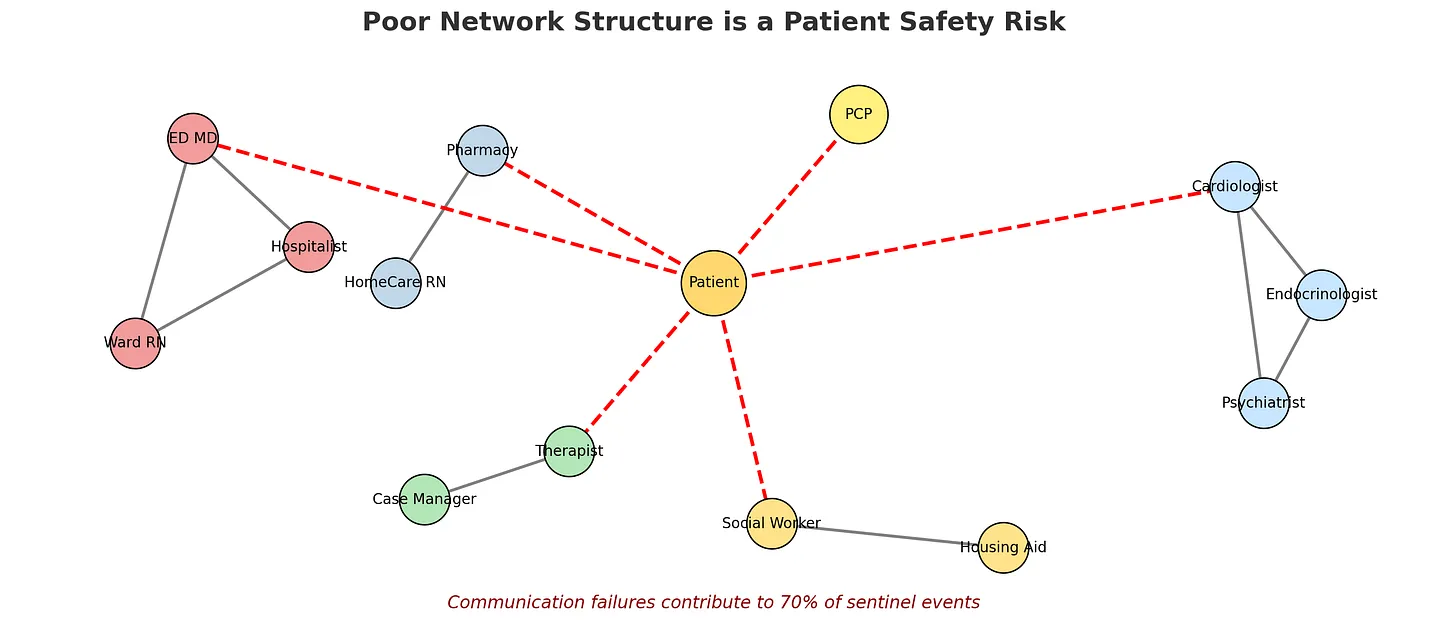

1. Communication Failure as a Root Cause of Harm

The Joint Commission has consistently reported that communication failures are a root cause in over 70 percent of sentinel events [8]. Studies of care transitions suggest that inadequate handoffs contribute to 50 to 70 percent of adverse events [9].

Network Interpretation: Each patient handoff represents a critical edge in the network. If these edges are unreliable, lacking structure, completeness, or a shared platform, information degrades as it travels. Larger, more fragmented networks multiply the opportunities for this decay.

2. The High Cost of Fragmented Readmissions

When a patient is readmitted to a different hospital, their care network effectively resets. The new team must reconstruct the patient's story from scratch, often without access to prior records or the institutional knowledge of what transpired during the initial admission.

Network Interpretation: Each hospital functions as its own dense subnetwork. Transferring a patient to a different one severs most existing informational edges, forcing the system to build a new, local network under time-sensitive, high-stakes conditions. The data shows this reset comes at a cost: higher mortality and longer stays [2].

3. The Unsustainable Burden on the Patient

For individuals managing multiple chronic conditions, the network's failure places an untenable burden on them. They are shuttled between disconnected specialist clusters and are forced to become their own primary information router. They are responsible for carrying medication lists, recounting medical histories, and reconciling conflicting advice.

Network Interpretation: The patient node is tasked with bridging structural holes that the professional network has failed to close. Any limitation in the patient's capacity, due to illness, health literacy, or language barriers, can lead to a catastrophic network failure. This manifests as medication errors, delayed diagnoses, or avoidable complications [4].

4. The Critical Role of Information Continuity

Information continuity is the seamless flow of core clinical information across settings and over time. It is the antidote to fragmentation [10]. From a network perspective, this is not merely about adding more communication, meaning more edges. It requires designing reliable, high-fidelity, and standardized edges that ensure essential knowledge reaches the right node at the right time. When this fails, care becomes unsafe.

Rewiring the System: Network-Informed Solutions

Network theory does not just diagnose; it prescribes. It directs us to intervene at the level of the system's structure.

1. Intentional Bridging: We must formally create and support edges between critical clusters. This can take the form of structured case conferences for high-risk patients, shared care plans, or embedding pharmacists within primary care clinics.

2. Empower, Do Not Overload, Central Nodes: Social network analyses often reveal that a handful of individuals, frequently nurses or managers, serve as de facto central hubs [11]. These individuals should be identified, provided with dedicated time and resources, and supported. They must not be left to become overstretched bottlenecks.

3. Engineer the Handoff: Programs like the I-PASS handoff bundle demonstrate that standardizing the structure of communication itself, the edges, can dramatically reduce medical errors [12]. We must treat care transitions as critical infrastructure deserving of deliberate design.

4. Map and Measure the Network: Using SNA, we can move from anecdotal impressions to data-driven maps of actual communication flows. This allows us to test interventions. Does adding a digital shared care platform increase density? Does a new liaison role effectively bridge structural holes? [6]

A Simulation: Seeing the Theory in Action

To make these concepts tangible, let us consider a simple computational model. We can simulate two networks:

A Fragmented Network with two tightly-connected clusters, for example, "Hospital" and "Community," with few bridges between them.

An Integrated Network with the same nodes, but with more cross-connections and perhaps a "Care Coordinator" node acting as a deliberate bridge.

In this simulation, "patients" move along a pathway of providers. A critical piece of information, such as a life-threatening drug allergy, is known only to the first provider. As the patient moves, the information spreads only between connected providers, and with a certain probability. If a provider acts, for example, by prescribing a medication, without knowing the critical information, an "adverse event" is recorded.

The results are consistently telling. The fragmented network yields a significantly higher rate of adverse events. The integrated network, by ensuring information flows more reliably to more providers, protects patient safety. This holds even when we vary the baseline reliability of communication. A better structure makes good communication more effective.

The structure of our healthcare networks is not a background issue; it is a primary determinant of patient safety. By consciously designing and supporting connected, resilient networks of communication, we can transform fragmented care into integrated healing.