Most adoption in networked environments is coerced. The Network Coercion Model simulates how social pressure overrides private preferences, and the results are consistent: 60 to 80 percent of participants adopt against their will. This raises a question for neuroethics that existing frameworks are poorly equipped to answer. If network topology can predict and override individual choice, where does agency actually reside?

The answer requires precision about what "coercion" means, how networks produce it, and why the distinction between voluntary and involuntary adoption collapses at specific density thresholds.

What Counts as Coercion

The simulation labels agents as "coerced" when they adopt despite negative private utility. But coercion is a contested concept in philosophy, and the claim that networks coerce demands more than a threshold model.

Robert Nozick (1969) defined coercion through a conditional structure: A coerces B when A threatens B with consequences that make B's alternatives unacceptable, and B acts accordingly. The threat need not be explicit. Nozick's account requires that the coercer intend to restrict options and that the target recognize the restriction. In network adoption, neither condition holds cleanly. No single node "intends" to pressure another. The pressure emerges from topology itself: from degree distributions, clustering coefficients, and the density of local ties.

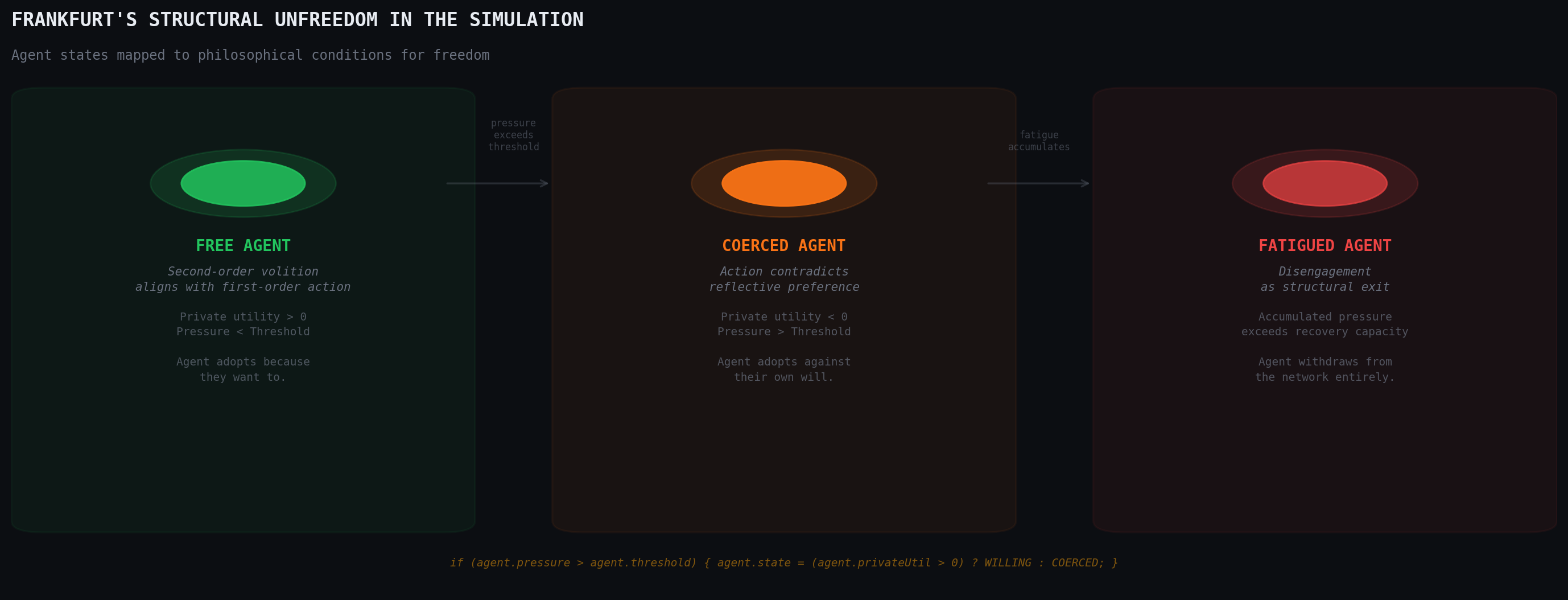

This is closer to what Harry Frankfurt (1971) called structural unfreedom. Frankfurt distinguished between first-order desires (wanting to adopt or not) and second-order volitions (wanting to want what you want). A person is free, on Frankfurt's account, when their first-order desires align with their second-order volitions. Network pressure disrupts this alignment. You adopt a platform you dislike because the social cost of refusal exceeds your private distaste. Your first-order action (adoption) contradicts your second-order preference (resistance). You act, but not as the agent you wish to be.

The simulation captures this disconnect with a single variable: private utility. When it's negative but the agent adopts anyway, Frankfurt's condition for unfreedom is met. The agent acts against their own reflective preferences.

This matters because it shifts the ethical question from "who is coercing?" to "what structural conditions produce unfreedom?" In networks, coercion has no author. It is an emergent property of connectivity.

The Simulation

Agents occupy positions in a network and carry four properties: private utility (how much they genuinely value adoption), a pressure threshold (how much social influence triggers state change), fatigue (accumulated exposure drain), and memory (past encounters with adoption pressure).

The governing equation:

Utility = PrivateUtility + β₁ × LocalPressure × e(−fatigue) + β₂ × GlobalPressure + β₃ × Memory − β₄ × Resistance

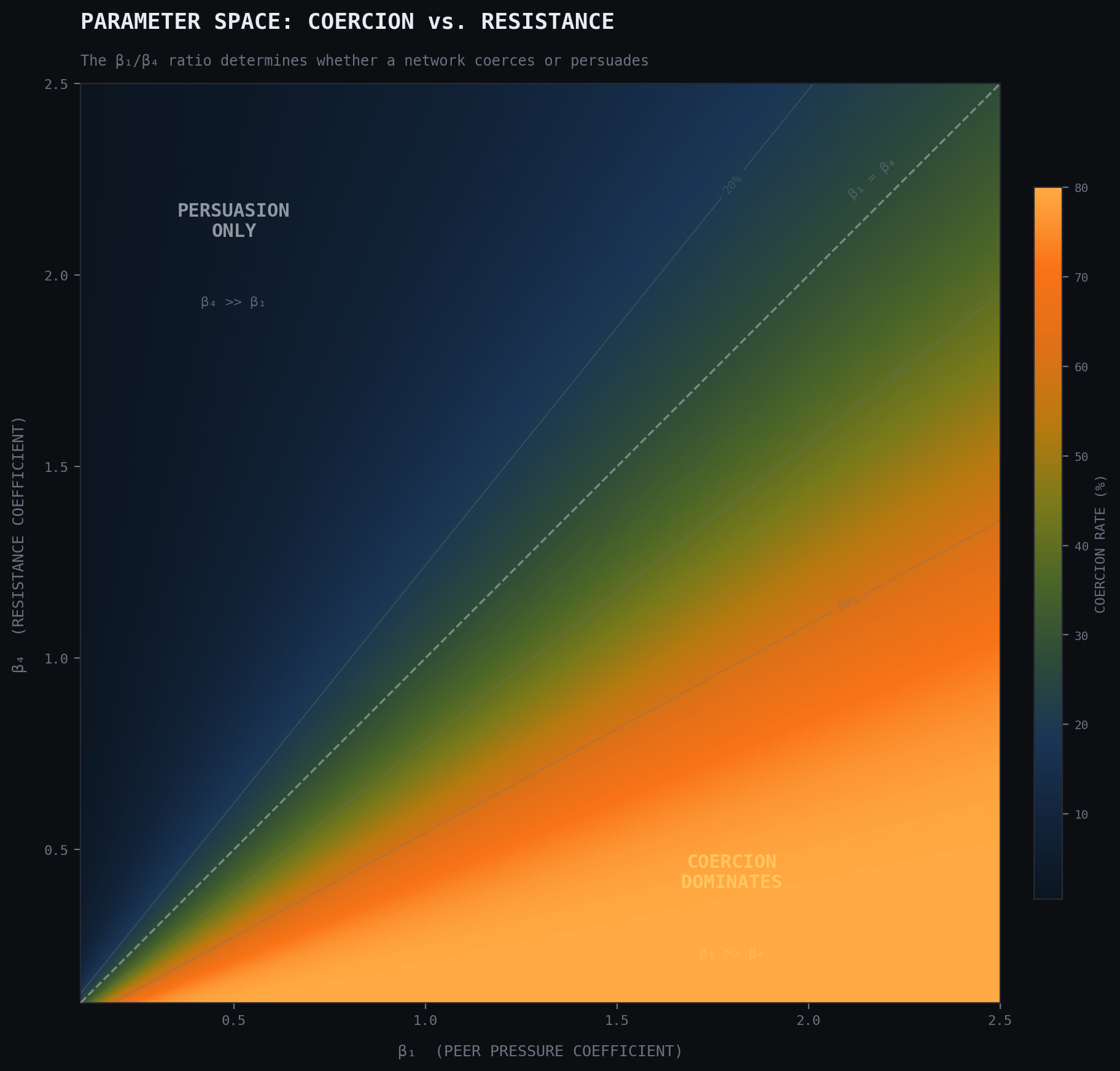

Each coefficient maps to a distinct social process. β₁ captures peer influence: the direct effect of adopted neighbors, exponentially decayed by fatigue. β₂ represents ambient cultural pressure, the signal that "everyone is doing this" regardless of your immediate circle. β₃ models accumulated exposure, the way repeated contact with an innovation lowers resistance over time. β₄ is the drag coefficient of individual conviction.

When the calculated utility exceeds an agent's threshold, adoption occurs. If private utility is positive, the adoption is coded as willing. If negative, coerced.

The model includes recovery dynamics. Fatigued agents disengage (red state), lose accumulated pressure, and may re-enter the susceptible population. This prevents the simulation from treating adoption as a one-way ratchet and introduces oscillation at the population level.

What the Parameters Reveal

The ratio of β₁ to β₄ determines whether a network coerces or persuades. When local pressure dominates resistance (β₁ >> β₄), even agents with strongly negative private utility adopt. When resistance is high relative to peer effects, adoption stalls or proceeds only through genuine converts.

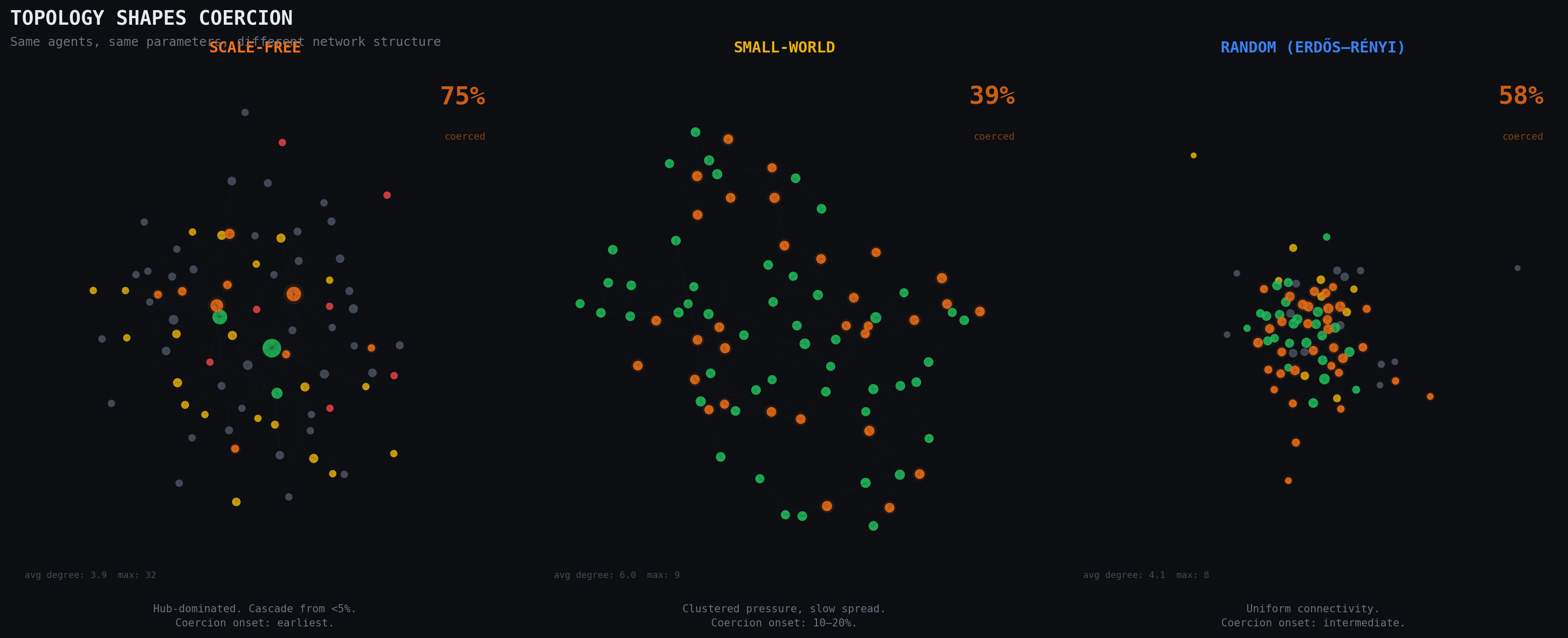

Network topology amplifies this. In scale-free networks, where a few nodes hold disproportionate connections, high-degree hubs transmit pressure to large portions of the network simultaneously. Coercion onset requires fewer initial adopters: sometimes under 5 percent (Watts, 2002). In small-world networks with high clustering, pressure is locally intense but spreads more slowly across clusters, requiring 10 to 20 percent for cascade. Random networks fall between these extremes.

The key finding across topologies: coercion is not proportional to adoption rate. It peaks in a specific window and then declines as the remaining non-adopters are either highly resistant or simply disconnected.

Visual States

The simulation renders five agent states. Gray nodes are unaware. Yellow halos indicate exposure: the agent is receiving pressure but has not yet crossed their threshold. Green marks willing adoption, where private utility is positive. Orange marks coerced adoption, where the agent's threshold was exceeded despite negative private utility. Red signals fatigue and disengagement.

The spatial distribution of orange nodes is not random. They cluster at the periphery of early adoption zones, in the boundary layer between committed adopters and the unexposed population. This is where structural pressure is highest relative to individual conviction: the agents close enough to adopters to feel pressure, but not committed enough to want what they're getting.

The Coercion Zone: 10 to 25 Percent

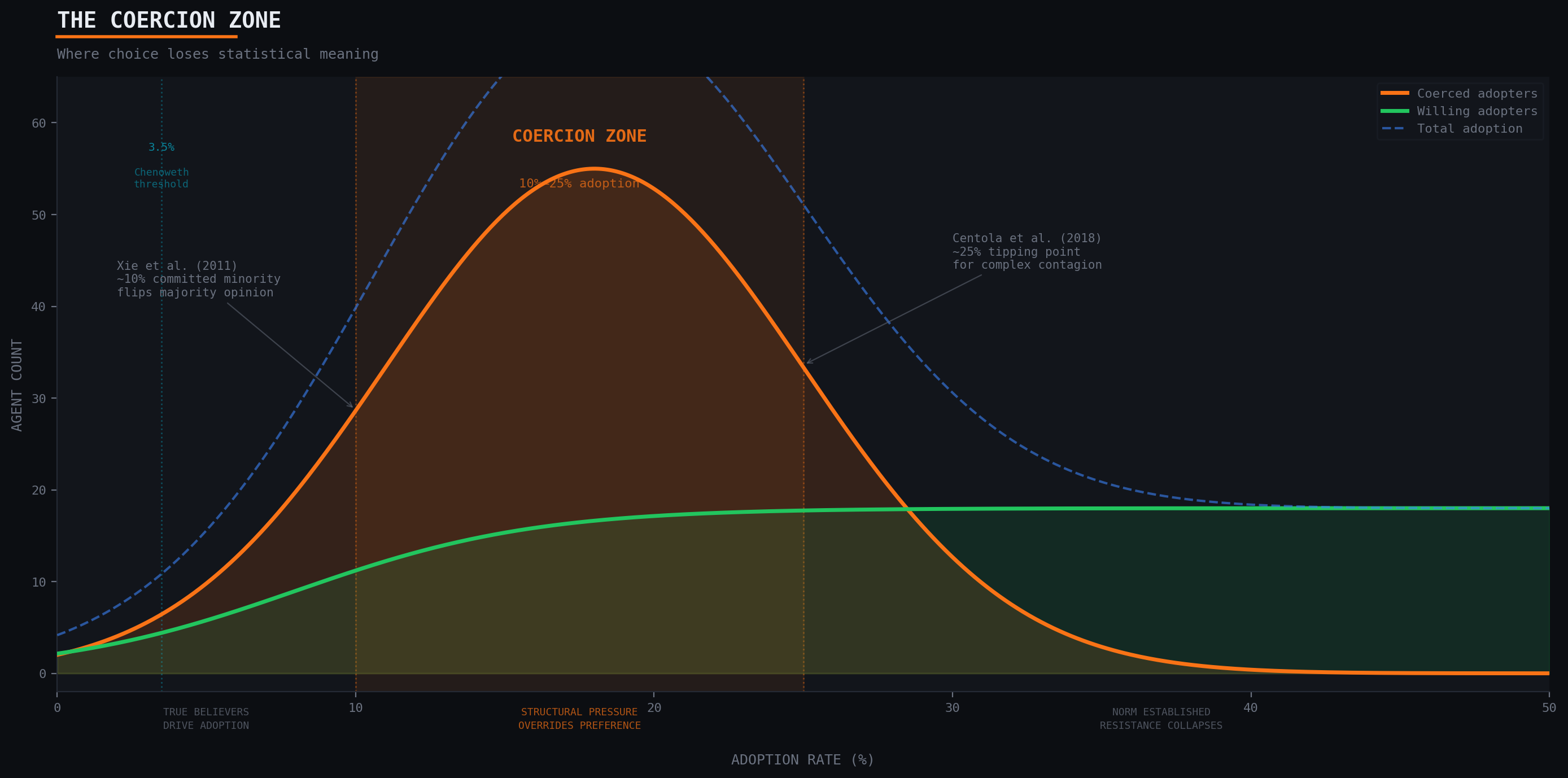

Between 10 and 25 percent adoption, the network enters what the model identifies as the coercion zone: the critical mass window where social pressure becomes self-reinforcing and the ratio of coerced to willing adopters inverts.

The empirical evidence for critical mass thresholds comes from multiple domains, and each study illuminates a different mechanism.

Xie et al. (2011) demonstrated through simulation and mean-field analysis that a committed minority of approximately 10 percent can flip majority opinion in a population. Their model used binary-state agents on random networks, showing that below 10 percent commitment, the minority opinion remains marginal; above it, consensus shifts rapidly. The mechanism is probabilistic: at 10 percent density, committed agents encounter uncommitted ones frequently enough to create local majorities that propagate.

Centola et al. (2018) moved this from simulation to experiment. Using an online platform where participants chose between competing social norms, they found the tipping point at roughly 25 percent. Below this threshold, committed minorities failed to shift the convention. Above it, the population flipped within a few rounds. The critical insight: this was complex contagion, requiring multiple exposures, not simple information spread.

The distinction between simple and complex contagion is central to the coercion argument. Centola and Macy (2007) showed that behaviors requiring social reinforcement (joining a protest, adopting a technology your contacts use, changing a health behavior) spread through wide bridges: clusters of connections that provide multiple, redundant signals. Simple contagion (news, information) spreads through any single connection. Coerced adoption is a complex contagion phenomenon. A single neighbor's adoption rarely pushes an unwilling agent past their threshold. It takes coordinated local pressure.

Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) found that nonviolent political campaigns succeed when they achieve 3.5 percent active, sustained participation. This lower threshold reflects a different mechanism: political action has high visibility and signals commitment intensity, so fewer participants generate proportionally more pressure. The 3.5 percent figure is a lower bound on cascade initiation, not the coercion window itself.

The simulation synthesizes these findings. Below 10 percent, adoption is driven by agents with positive private utility: true believers, early adopters, people with genuine preference for the innovation (Rogers, 2003). Between 10 and 25 percent, the balance shifts. Social pressure from existing adopters begins exceeding the thresholds of agents with negative utility. The cascade accelerates, but most of the acceleration comes from unwilling participants. Above 25 percent, the new norm is functionally established. Remaining non-adopters face a binary between adoption and social isolation, and resistance collapses not because preferences change but because the cost of non-adoption becomes prohibitive.

The 10 to 25 percent window is where the concept of "choice" loses statistical meaning. Individual decisions become predictable from network position and local adoption density alone.

Networks as Cognitive Architecture

The claim that social networks function as cognitive systems is not metaphorical. It draws on a specific philosophical tradition.

Clark and Chalmers (1998) argued that cognitive processes extend beyond the skull when external resources play the same functional role as internal mental states. Their "parity principle" holds that if an external process, were it occurring in the head, would count as cognitive, then it counts as cognitive regardless of where it occurs. A notebook that stores beliefs functions as memory. A calculator that performs arithmetic functions as computation.

Social networks satisfy this criterion. When an individual's adoption decision is determined by the states of their neighbors, the network is computing the decision. The local pressure term in the simulation (β₁ × LocalPressure × e(−fatigue)) is functionally equivalent to a weighted sum across inputs: the same operation a neuron performs. Connections are synapses. Adoption events are firing patterns. The network processes information and produces behavioral outputs.

Edwin Hutchins (1995) documented this empirically in his study of naval navigation teams. He showed that cognitive labor in complex tasks is distributed across individuals and artifacts, and that the "unit of analysis" for cognition is the system, not any individual participant. No single crew member navigates the ship. The navigation emerges from the interactions between crew members, instruments, charts, and communication protocols.

The simulation extends this logic to norm adoption. No single agent "decides" to create a norm. The norm emerges from the interaction between topology, thresholds, and pressure dynamics. The network is the cognitive system. Individual agents are components.

This reframing has direct consequences for neuroethics. If we accept that networks perform cognition, then the study of how technology affects the brain must include how network topology structures decision-making. The simulation makes this concrete. When enough neighbors adopt, an individual's state changes through a process that is functionally computational, not volitional. The network computes the decision before the agent deliberates.

Neil Levy (2007) argued that neuroethics should concern itself with any system that modulates cognitive function, not only direct neural interventions. Social networks qualify. They modulate decision-making by restructuring the information and pressure environment in which choices occur. A network that amplifies social proof is doing cognitive work: filtering signals, weighting inputs, producing behavioral outputs.

This is neurocomputational ethics. The network becomes cognitive architecture that bypasses volition, and the ethical question becomes: who designs the architecture?

The Code Makes the Argument

One conditional captures the entire moral problem:

if (agent.pressure > agent.threshold) {

if (agent.privateUtil > 0) agent.state = STATE.WILLING;

else agent.state = STATE.COERCED;

}When pressure exceeds preference, autonomy collapses into a binary classification. The code is deterministic: above threshold, the agent switches. Below, they don't. Human decision-making is probabilistic, messy, subject to mood and context and the specific argument your neighbor made over coffee. The simulation strips this away deliberately. It asks: if we reduce agency to its structural minimum, what does network topology alone predict?

The answer is that topology predicts 60 to 80 percent of adoption outcomes independent of private preference.

This transforms "manufactured consent" from a rhetorical concept into a measurable process. Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman (1988) used the term to describe how media systems produce public agreement through structural filtering rather than overt censorship. The simulation operationalizes this: consent is manufactured when network structure pushes adoption rates past the coercion threshold, producing behavioral compliance that looks voluntary from the outside but registers as coerced at the individual level.

The gap between the code's determinism and human reality is itself informative. Real humans sometimes resist past their threshold. They find workarounds, form counter-networks, develop ironic compliance. The simulation's 60 to 80 percent coercion rate is likely a ceiling. But even at half that rate, the ethical implications hold. If 30 to 40 percent of adoption in networked systems is structurally coerced, the assumption of individual consent that underlies platform governance, technology policy, and market regulation is compromised.

Distributed Responsibility and Conditional Agency

If network topology predicts individual choice with probability approaching 1 as density increases, personal consent becomes conditional on structural context. This shifts the ethical framework from autonomy (the capacity for self-governance) to what we might call conditional agency: free will modulated by topology and pressure, genuine in some configurations, illusory in others.

The responsibility implications follow directly. In a system where no single actor coerces but the structure produces coercion, who bears moral responsibility?

Traditional ethics assigns responsibility to agents with intent. Tort law looks for proximate cause. Neither framework handles emergent coercion well. The platform designer didn't intend to override anyone's preferences; they optimized for engagement. The early adopter didn't mean to pressure holdouts; they just liked the product. The algorithm didn't choose to amplify social proof; it maximized a metric.

But the coercion happened. The simulation shows it happening, tracks which agents were coerced, identifies the network positions most vulnerable to structural pressure. If we can predict and measure coercion, the absence of individual intent becomes insufficient defense.

Systems that amplify social influence through algorithmic curation, network-effect lock-in, or social proof mechanisms must be treated as cognitive infrastructures. They are not neutral conduits for human choice. They are architectures that produce specific patterns of adoption, and those patterns include systematic coercion of agents whose private preferences oppose the emergent norm.

Design Implications

If autonomy is a design variable, then three interventions follow from the model.

First, transparency about network pressure. The simulation can estimate coercion probability for any given network position and adoption rate. Showing users their position in the pressure landscape (how much of their adoption behavior is driven by peer effects versus genuine preference) would make structural coercion visible. Visibility does not eliminate pressure, but it restores the second-order reflection that Frankfurt identified as the condition for freedom.

Second, friction at the coercion threshold. The 10 to 25 percent window is identifiable in real-time. Platforms could introduce deliberate slowdowns during cascade phases: confirmation steps, cooling-off periods, prompts that surface private preference before social pressure resolves the decision. This is the design equivalent of informed consent.

Third, exit architecture. The simulation assumes agents have no exit option; they can disengage through fatigue but cannot leave the network. Real systems could reduce coercion by lowering exit costs: data portability, interoperability standards, reduced switching penalties. When leaving is cheap, the pressure to stay despite negative utility drops. The coercion zone narrows.

Each of these is a testable modification to the simulation. Running the model with transparency, friction, and exit parameters would generate predictions about how much each intervention reduces coercion rates, predictions that could then be validated against real platform data.

Limitations

The model assumes agents have fixed private utilities and thresholds. Real preferences shift through deliberation, persuasion, and experience. An agent who initially resists a technology may come to value it after coerced adoption. The simulation cannot distinguish between this (preference formation) and simple capitulation (behavioral compliance without preference change). Both register as continued adoption.

The model also lacks strategic behavior. Real agents form coalitions, coordinate resistance, and engage in signaling. A group of holdouts who publicly commit to non-adoption can shift local pressure dynamics in ways the current model does not capture.

Finally, the deterministic threshold mechanism overstates the sharpness of the coercion boundary. Human adoption decisions involve stochastic elements, emotional states, and contextual factors that create a probability distribution around the threshold rather than a hard cutoff. A probabilistic variant of the model would likely show a wider, fuzzier coercion zone with lower peak coercion rates but longer duration.

These limitations do not invalidate the core finding. They bound it. The model demonstrates that network structure can produce coerced adoption at scale. The precise rates and boundaries are approximations. The structural mechanism is real.