"Soylent Green is people!"

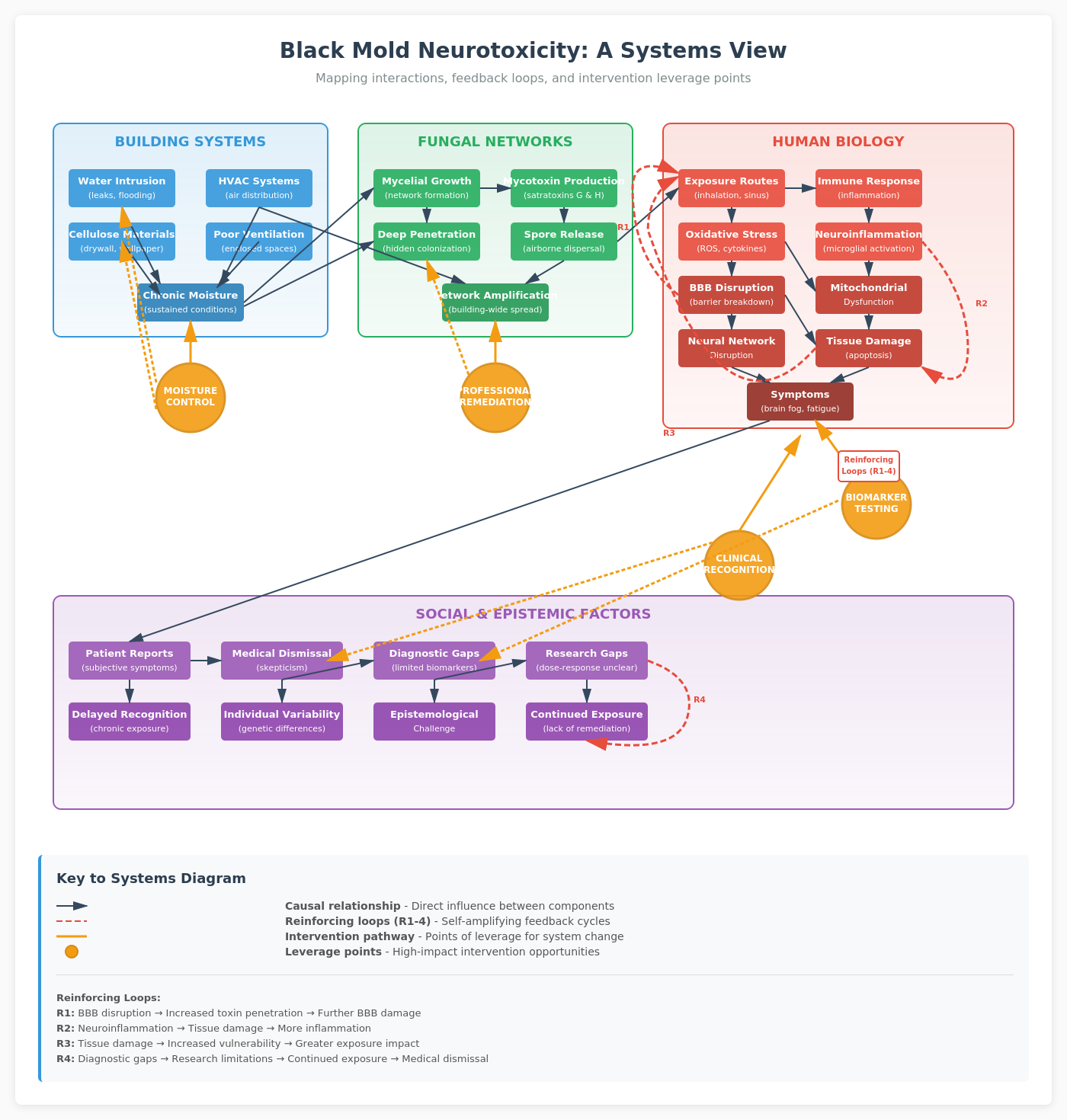

In my work as a computational neuroscientist, I study how networks emerge, organize, and fail. From neural circuits to social systems, network architecture determines function. But there's a network story I've been reluctant to tell because it sits in a controversial space: the neurotoxic effects of indoor mold exposure, specifically from Stachybotrys chartarum, commonly known as black mold.

Although there has been recent research (2024-2025) provides mounting evidence for mycotoxin-induced neurotoxicity, there still has been quite the controversy around this topic. The controversy around mold toxicity is largely social: people who report cognitive symptoms from water-damaged buildings are often dismissed, however, this is an evolving field of inquiry that will hopefully elucidate better mechanisms as time goes by. Understanding the network dynamics at play, both in fungal growth and in neural disruption, might help legitimize these experiences while grounding them in rigorous science.

*Full disclosure: my own health problems, immune sensitivities, and chronic exposure to black mold throughout my graduate education (Master's and Doctoral studies) over 10 years, and a recent health attack led me to realize the full extent of this problem.

Fungal Networks as Adaptive Systems

Before we discuss disruption, we need to understand what we're dealing with. Fungi don't grow like plants or bacteria. They develop as interconnected networks of thread-like hyphae that branch, fuse, and reorganize in response to resource availability. These mycelial networks solve optimization problems in real-time: finding food sources, transporting nutrients across distances up to several meters, and adapting their architecture based on damage or opportunity. In this way, mycelial networks exemplify plasticity in action which is the capacity of a living system to reorganize itself dynamically in response to information, damage, and opportunity.

Now, back to black mold… Stachybotrys chartarum belongs to this class of network-forming organisms. It thrives on cellulose-rich materials like drywall and wallpaper in water-damaged buildings. Unlike faster-growing molds, S. chartarum is a slow colonizer, but it excels in environments with constant moisture, large temperature fluctuations, and minimal competition. Its mycelial network can penetrate deep into building materials, creating what amounts to a three-dimensional distributed organism hidden behind walls.

The network structure itself is in itself, pretty cool. Fungal mycelia display properties analogous to efficient transport networks: they minimize path length while maintaining redundancy, they reinforce high-traffic routes while recycling underutilized connections, and they exhibit something resembling memory in their growth patterns. Research on related species shows that mycelial networks can "remember" the direction of previous growth and make resource allocation decisions that suggest rudimentary information processing (see references for more details).

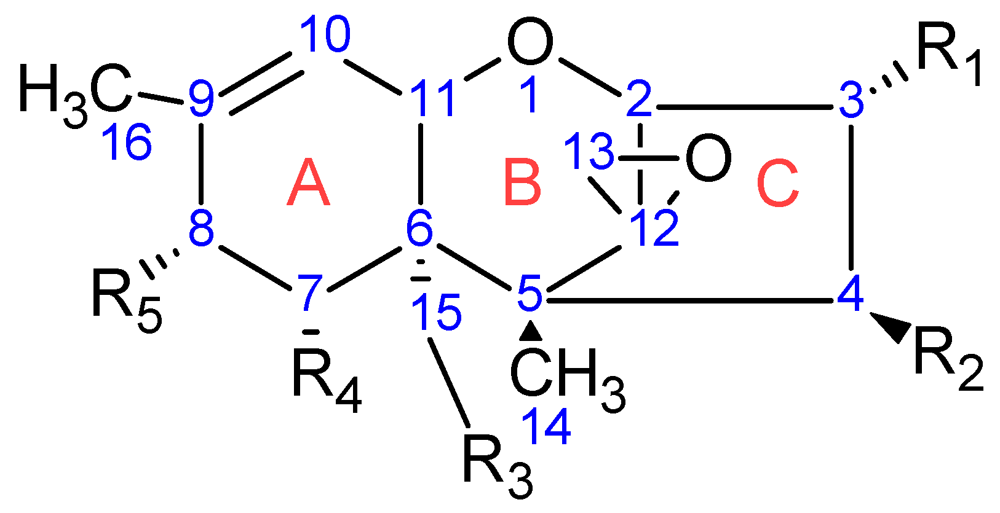

But here's where the story gets darker… Some chemotypes of S. chartarum produce macrocyclic trichothecene mycotoxins, particularly satratoxins G and H. These secondary metabolites are not accidental byproducts. They're potent protein synthesis inhibitors that the fungus likely evolved as chemical warfare against competitors and predators.

When concentrated in spores and released into indoor air, they become neurotoxic agents capable of disrupting the very network structures I study: neural circuits.

Mechanisms of Mycotoxin Neurotoxicity

The neuroscience literature on mycotoxins has exploded in recent years. A 2025 scoping review by Abia et al. identified multiple pathways through which common mycotoxins, including those from S. chartarum, induce neurotoxicity. The mechanisms read like a catalogue of neural network failure modes.

First, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation. Mycotoxins like aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin A, and trichothecenes increase reactive oxygen species in neuronal cells, triggering pro-inflammatory cascades. Elevated levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α create a neuroinflammatory environment that disrupts normal synaptic function. This isn't subtle damage. Studies show increased microglial activation through ERK and p38 MAPK pathways, shifting cells toward M1 inflammatory phenotypes.

Second, mitochondrial dysfunction. Fumonisin B1, another mycotoxin common in mold-contaminated environments, disrupts sphingolipid metabolism, which is essential for maintaining neuronal membrane integrity and signal transduction. Impaired mitochondrial function means energy deficits in neurons, leading to apoptosis (a form of programmed cell death) in vulnerable populations like olfactory sensory neurons. Animal studies show that intranasal instillation of satratoxin G causes maximum atrophy of the olfactory epithelium within three days, with clear evidence of programmed cell death.

Third, neurotransmitter dysregulation. Multiple studies document alterations in serotonin, dopamine, and GABA systems following mycotoxin exposure. The clinical manifestations align with what people report: mood changes, cognitive impairment, memory deficits, brain fog, anxiety, and depression. A 2025 paper by Hoxha and colleagues found that mycotoxin exposure was linked to neuropsychiatric symptoms in vulnerable populations, drawing on earlier work showing that the neuropsychological profile of mold-exposed patients can resemble mild traumatic brain injury.

Fourth, blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption. Aflatoxins are documented to compromise BBB integrity, allowing peripheral inflammatory signals to penetrate the central nervous system. This creates a cascade effect: initial toxic exposure leads to barrier breakdown, which permits continued access for toxins and inflammatory mediators, which further damages neural tissue.

Neural Networks as Vulnerable Architectures

Here's where network science becomes critical. Neural systems are not resilient to all forms of attack. They're optimized for certain kinds of perturbations (synaptic noise, moderate cell loss) but vulnerable to others (systematic inflammation, metabolic disruption, coordinated apoptosis).

Consider the parallel to graph theory. A neural network maintains function through redundancy and small-world properties: local clustering of connections combined with strategic long-range links. This architecture supports rapid information transfer and fault tolerance. But it's vulnerable to targeted attacks on hub nodes and to diffuse damage that disrupts metabolic support structures.

Mycotoxin-induced neuroinflammation represents exactly this kind of diffuse, metabolic attack. It doesn't need to kill specific neurons. It degrades the support infrastructure: astrocytes, microglia, vascular endothelial cells, and mitochondria. The result is a network that remains structurally intact but functionally compromised. Signals propagate more slowly, synaptic plasticity decreases, and cognitive processing becomes less efficient.

The symptoms people describe align perfectly with this model: brain fog, concentration problems, memory issues, mental fatigue, and difficulty with executive function.

These aren't vague complaints, but the expected output of a neural network operating under metabolic constraint and chronic low-grade inflammation.

Building Networks That Build Networks

There's a deeper irony here. Fungal networks and neural networks are both solutions to similar computational problems: how to efficiently explore and exploit a complex environment with limited resources. Both use branching structures, both maintain distributed information processing, both exhibit plasticity in response to environmental signals.

But when fungal networks colonize our built environment, they can deploy chemical agents that disrupt our neural networks. The mycotoxins that protect fungal territory become neurotoxins that degrade human cognition. This is network warfare across kingdoms, mediated by secondary metabolites that took millions of years of evolution to optimize!!

The fungal perspective is instructive. S. chartarum doesn't "want" to harm humans. It's optimized for survival in environments with abundant cellulose and moisture, conditions that, unfortunately, describe many modern buildings with water damage. Its mycelial network grows to maximize resource extraction and minimize competition.

Trichothecenes are secondary metabolites that likely evolved as adaptive chemical defenses and virulence factors, but they happen to have severe, often neurotoxic consequences for organisms with nervous systems.

From a network perspective, both fungal mycelia and building HVAC systems are distribution networks. Air handling systems, designed to efficiently move conditioned air throughout a structure, become highways for spore distribution when contaminated.

A single growth site behind drywall can release spores into the airflow, dispersing them throughout an entire building. This is network amplification: a localized fungal network exploits an architectural network to maximize its reproductive reach.

Temporal Dynamics and Chronic Exposure

One reason mold-related illness remains controversial is timing. Acute mycotoxicosis, like the cases of pulmonary hemorrhage in infants linked to S. chartarum exposure in Cleveland during the 1990s, is easier to identify causally. But chronic low-level exposure presents differently.

Neuroinflammation accumulates over time. A 2014 study found that sinuses can harbor mold colonies even after a person leaves a contaminated environment, continuously releasing mycotoxins and maintaining inflammatory signaling. This creates a feedback loop: ongoing exposure triggers immune responses, which create oxidative stress, which damages tissue, which becomes more vulnerable to continued toxin effects.

The neural effects are cumulative too. Cognitive decline from chronic inflammation doesn't present as a single catastrophic event. It manifests as gradually worsening symptoms that people adapt to until they realize they can no longer perform at their baseline level. The temporal dynamics make causal attribution difficult, which contributes to medical dismissal.

The Epistemological Challenge

This brings us to the core problem: how do we study network effects that are distributed across space and time, with high individual variability, in systems we can't directly observe?

There are some research tools that do exist to figure out this mystery. Urinary mycotoxin biomarkers can detect exposure. Cytokine panels can measure neuroinflammation. Neuroimaging can reveal network-level changes in brain connectivity. But deploying these tools requires believing the complaint is legitimate, and the social dynamics often work against this!!!!

Just a small note, but there's also the problem of mechanistic specificity. Not all S. chartarum produces mycotoxins. Even among toxigenic strains, mycotoxin levels vary with substrate composition and environmental conditions. Not all individuals exposed will develop symptoms, likely due to genetic variations in detoxification enzymes and immune response. The dose-response relationship for chronic low-level exposure remains poorly characterized.

From a network science perspective, this is an inference problem. We're trying to identify causal relationships in a system with multiple interacting components (fungal networks, building systems, human physiology, individual genetics) and significant measurement noise. The traditional epidemiological tools struggle with such systems, which is partly why controversy persists.

Implications for Built Environments

If we take the network perspective seriously, the implications for architecture and building management become clear. Buildings are not static containers. They're ecosystems with microbial communities, moisture dynamics, and airflow patterns that create niches for various organisms.

Water damage creates those niches. A leak behind a wall establishes the constant moisture conditions S. chartarum requires. The cellulose in drywall provides the carbon source. The enclosed space reduces competition from faster-growing molds. Add poor ventilation, and you have ideal conditions for a toxigenic fungal network to develop and persist.

Prevention requires thinking in terms of network resilience. Moisture control means more than fixing leaks. It means understanding building envelope physics, managing vapor barriers, and designing HVAC systems that prevent condensation. It means regular inspection of hidden spaces where fungal networks can establish before becoming visible.

Remediation requires more than surface cleaning. Fungal mycelia penetrate materials. They form networks that can extend meters from the visible growth site. Professional remediation involves removing contaminated materials, addressing moisture sources, and using negative air pressure to prevent spore dispersal during the process.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The scientific evidence for mycotoxin neurotoxicity is growing stronger, with several mechanisms now increasingly well documented, and the clinical presentations often aligning with predicted effects of chronic neuroinflammation and metabolic disruption. What remains unclear is the dose–response relationship for chronic low-level exposure in diverse populations and the most effective diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

As a network scientist, I see this as a problem requiring integrated systems thinking across scales. At the microscopic level, we need better understanding of mycotoxin kinetics and cellular responses. At the neural network level, we need longitudinal studies of cognitive function and brain connectivity in exposed populations. At the built environment level, we need better moisture monitoring and air quality assessment. At the social level, we need to take patient reports seriously while maintaining scientific rigor!

The fungal networks growing in water-damaged buildings are doing what evolution designed them to do: explore, exploit resources, and defend territory. The neural networks in people occupying those buildings are experiencing disruption that, while often subtle, can significantly impact quality of life. Both are network phenomena. Both deserve serious scientific attention.

The controversy around "toxic mold" isn't helped by overblown media coverage or by dismissive medical responses. What's needed is careful, methodologically sound research that acknowledges the complexity of the system while working to establish clear causal relationships and effective interventions.

If you're experiencing cognitive symptoms and have been exposed to water-damaged buildings, you're not imagining it. Your neural network may be responding to a real environmental insult. The challenge is finding medical professionals who understand both the science and the limitations of current diagnostic tools. The research base is growing. The mechanisms are being elucidated. And the network perspective helps explain why these effects are real, complex, and often difficult to characterize.